I can tell you from experience that not all fowl pox in your flock is as foul as it sounds. Yes – it’s frightening to see your pretty poultry marred with ugly scabs. It’s also hard to see them seem somewhat sullen for a few days while their immune systems fight the virus.

Thankfully, though, in most cases, good basic care will get your flock safely through and onto greener pastures in no time. The tricky thing about this virus though is that it’s not always easy to spot the early signs and your options for treatment are limited.

So, I’d like to start by sharing my personal experience with fowl pox to give you a sense of how the virus infects your flock and what to expect when it does. Then, I’ll get into research-based details about the virus to help you manage and possibly prevent it in your flock.

Let’s get started!

Early Signs of Fowl Pox

For me, the outbreak started with my 6-year-old Bourbon red turkey named Woodford. One morning last summer, when I took Woodford breakfast, he only raised his feathers to half-mast. Normally he goes into full drum mode the second he sees me.

I knew instantly something was wrong. Also, his eyes, usually so bright and flirtatious (male turkeys are total flirts!), seemed much less glossy than normal. However, he ate and drank and had no other signs of illness.

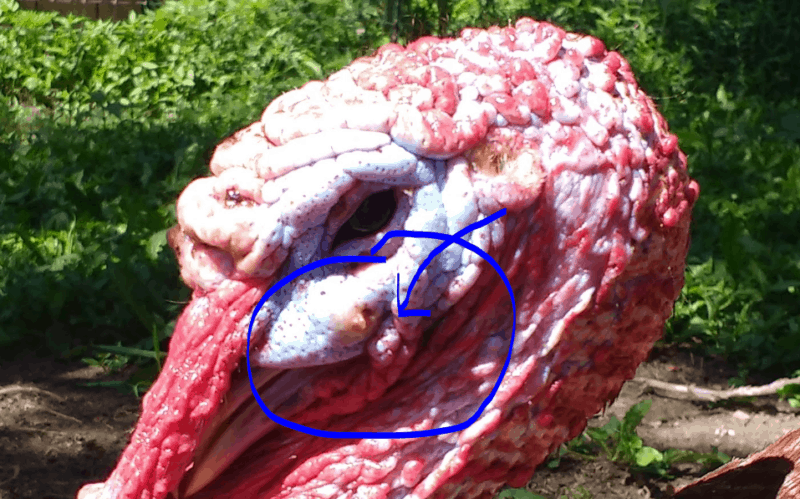

Since it’s not really in my homesteading budget to rush a sick turkey to the vet, I made the call to watch and wait. I wrote a few notes on his condition, took the above photo for reference, and then checked on him regularly to see if there were any changes.

Isolation

I should also mention that Woodford lives with our goats and is at least 500-feet away from my other poultry. So, I didn’t need to further isolate him. However, if he’d been in with other birds, I would have separated him just in case his illness proved contagious.

Advanced Symptoms

The low energy and eye dullness went on for 2 days before the first signs of pox appeared. They started like little light-colored freckles widely scattered the skin on his head, wattle, and snood.

By the next day, a few had grown into sores the size of screw-heads and one was a bit bigger. Very soon after that, they looked dry and scabby. One looked like a popped pimple. One formed on his eyelid and looked particularly bad because it made his eye droop.

Diagnosing the Virus

I have to tell you, until this event, I’ve had no diseases or viruses in my flock. So, I had to hit the books to figure out what I was dealing with.

Specifically, I found the answer in The Chicken Health Handbook by Gail Damerow. Then I did additional research to confirm my suspicion using online references.

Diagnoses: Dry Pox

After all that, I was pretty sure I was dealing with my first case of Dry Pox. This is the more common of the two kinds of fowl pox that commonly afflict backyard flocks. Still, since this was brand new for me, I sent my veterinarian (who is also a pal) an email to confirm my suspicions.

Of course, he couldn’t give me a 100% positive confirmation without doing a laboratory test. Even so, he said it seemed quite probable that it was dry pox. He just told me to monitor my turkey. Also, just in case his symptoms worsened, he gave me the contact information for a veterinarian who had expertise in avian diseases.

Note: Many vets won’t take poultry patients because there is an extremely limited number of approved treatments available. If you find a vet who knows about poultry, hang on to their number!

Duration of the Virus

Woodford looked a bit rough for several more days. However, within a week he drummed again. It took a few more weeks for his scabs to heal fully. However, now he’s as lovely as ever!

Other than giving Woodford his normal food and water and a few extra high protein treats, there’s one more thing I did to ease his suffering. I rubbed olive oil on his pox.

I know it might sound crazy, but he loved it. My vet laughed at me for doing it, but he said it seemed like a perfectly reasonable treatment for dry pox.

I had also read that cleaning up the scabs was a good idea to prevent spread. However, Woodford wanders over a quarter acre pasture. So, that suggestion was absurd. Once he was better, I cleaned out his roost area. Still, that was the extent of what I could realistically do in terms of hygiene.

Contagious Spreading

I wish that were the end of the story, but 3 weeks later, I saw the first signs of dry pox in my chicken flock. The chickens live over 1500-feet away from Woodford’s pasture and had no contact with him.

They also never showed those early signs of lethargy and were laying eggs like champs. So, it wasn’t until I saw the actual pox on my 2 Delaware chickens that I knew they had fowl pox.

After that, two other chickens got it over a 2-week period. Other than having visible pox, none of the infected chickens showed any signs of illness and all four continued to lay as usual.

My other 11 chickens didn’t get it and the 22 ducks in the same area also didn’t get it. The only special care I gave them was to change their water twice a day.

Now that I’ve taken you on a journey through my experience with fowl pox, let me highlight some important takeaways from this story and fill in a few details I learned in my research.

What is Fowl Pox?

Fowl pox is the common name for Avipoxvirus. It comes in two forms – dry (skin or cutaneous) and a wet (diphtheritic) form. Here are the key differences between the two forms.

1. Dry Pox

Dry pox is the most common type of pox infection for poultry. It shows up on unfeathered external skin parts. They start as pale-colored dots and then grow into darker, larger spots. Eventually, they dry out and scab over. Larger sores may look a bit warty or like a blister.

It has a low mortality rate and is generally not considered a serious health issue for a flock. Dry pox can pose serious risks to poultry who develop secondary infections or have underlying health risks. As such, you’ll have to pay close attention to the overall health of your flock until they are fully recovered.

2. Wet Pox

Wet pox infects the mucous membranes. They also start as pale marks in areas such as inside the mouth. This can make them harder to spot in the earlier phases.

They can also migrate down further into the throat and crop area. In severe cases, the pox can grow large enough to prevent swallowing. Your poultry can then become dehydrated and undernourished, and their overall health can deteriorate quickly. Thankfully, wet pox is less common than dry pox.

With wet pox, you must take additional steps to monitor your flock to make sure they are drinking and eating regularly. Isolating an infected bird and monitoring food and water consumption rates is one way to do this.

Or you can weigh birds to make sure they aren’t losing weight. If you use the weighing method, weigh at the same time each day, such as in the morning before they eat.

Fowl Pox Treatment

There is no cure for fowl pox. However, there are a few things you can do to improve your flock’s odds of a speedy recovery and to reduce the risk of infection.

Here are some simple suggestions in the Chicken Health Handbook.

- Applications of a topical antiseptic (e.g. Betadine) can be used directly on the pox.

- Warm saline solution can soften mouth sores so you can remove them to enable eating.

- Adding a tablespoon of vinegar per gallon of water will help sanitize shared water sources.

She also suggests that in severe cases a broad-spectrum antibiotic may prevent infections. Of course, for organic homesteaders, you must do additional research before considering antibiotics for livestock.

As I mentioned, Woodford loved the olive oil. So, any kind of moisturizing aid can offer comfort for dry pox in particular.

Fowl Pox Vaccination

It’s also possible to vaccinate poultry to prevent fowl pox. Hatcheries will not normally provide this vaccination for you. So, you would need to obtain the vaccine and administer it yourself or have your veterinarian do it. For maximum protection do this when birds are between 12-16 weeks of age.

Additionally, for this vaccine, you need to do a follow-up check to make sure your flock members reacted to the vaccination site to ensure it is working. There are also risks for infection at the vaccination site.

If your area is at high risk for fowl pox, then this is something worth considering. If you plan to administer it yourself, also make sure you are up to speed on all your homestead vaccination safety procedures.

Finally, since this virus is slow spreading, according to Gail Damerow, you can also vaccinate uninfected members of your flock when the virus makes its appearance. The vaccination might take quickly enough to prevent them from suffering the full-blown virus later.

Risk Reduction

Now let’s talk about another way you can reduce your risk for having the virus run through your flock. This one will also make life overall better for you and your fine feathered friends.

Vector-borne Disease

Both versions of the virus are what’s called a vector-borne disease, and there are 3 basic things that must happen for it to infect your flock.

- The virus must be circulating in the area where you have your flock.

- You need an open wound.

- The virus must come in contact with the open wound.

The most common way fowl pox is spread is by mosquitos. They pick it up from one host in your area. Then, they create a wound when sucking blood from your poultry. Afterward, that puncture wound becomes the point where the virus spreads to other areas.

Experts say that mosquitos can keep the virus in their salivary glands for up to 8 weeks. So, that might explain why it took 3 weeks for the virus to move from my turkey to my chicken flock. However, it’s also the reason why scouring your coop at the first signs of infection won’t stop the spread of this virus.

– Mosquito Control

Instead, focus your energies on reducing your mosquito population. Get rid of standing water. Grow mosquito repelling plants. Use traps and other simple solutions to minimize risk.

You obviously can’t get rid of all mosquitos. However, by limiting the number of them that might carry the virus and have access to your chickens, you can help control the spread.

– Good Hygiene

Of course, good hygiene is just a wonderful idea in general. So, you may still have to do a general cleanup and refresh your bedding when those scabs fall off as a matter of course. Changing your litter with greater frequency in the few weeks following an outbreak can also help reduce risks for reinfection.

It is Not Chickenpox

Now, before we wrap up – you’ve heard of chickenpox (varicella-zoster), right? We humans get it, usually as children. Once we had it, we tend to be immune.

Well, I bring this up because fowlpox has absolutely no relationship to chickenpox. Fowlpox (avipoxvirus) comes from the Poxviridae family, whereas chickenpox is a Herpesviridae family virus. Fowlpox only infects birds and chickenpox (oddly) only infects humans!

So, despite the confusing common nomenclature – chickenpox doesn’t come from chickens. Also, thankfully, fowl pox isn’t zoonotic which means it can’t spread to humans. This is one of the poultry viruses you can safely treat at home without the aid of a veterinarian.

Please note, there are other poultry diseases such as avian flu, which can be contagious to humans. Before you attempt to treat a chicken illness, make sure you can identify it with certainty or consult your veterinarian for safety.

The other good news is that like chickenpox, recovered poultry will probably be immune to fowl pox should those pesky mosquitos come to spread the virus again. In some rare cases, though, the virus goes dormant in a bird and then recurs later.

Final Thoughts

Fowl pox, in the grand scheme of poultry viruses, is one of the easier diseases for a flock to face and recover from. That doesn’t mean there will never be losses. Some birds might simply have underlying conditions that make them more prone to severe infections.

Still, I know you’ll give your flock the best care possible. Caring is really the most important thing you can do to help see them through the challenge.