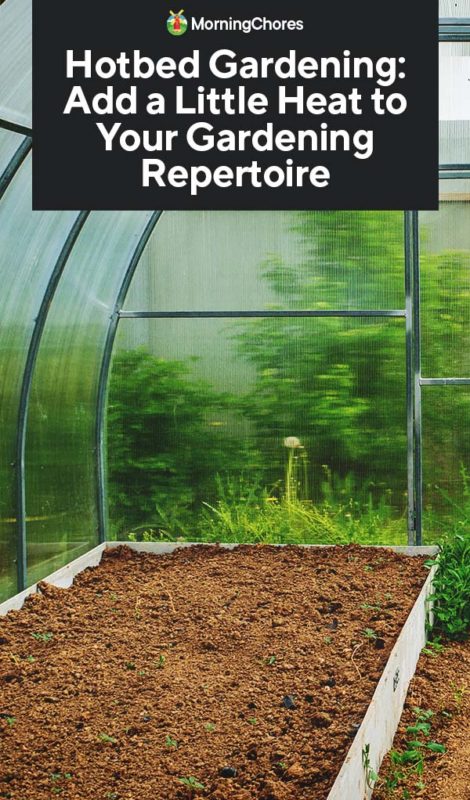

When I first got a greenhouse, I thought it would be great for starting seeds. Unfortunately, even though it is hot during the day, nighttime temperatures often drop below freezing. That made it impossible to start warm weather crops like tomatoes and eggplant early unless I heated the greenhouse.

I didn’t want to have to run an electric line to our greenhouse or become dependent on propane gas to get a jump on spring. So, instead, I harnessed the power of compost to start my seeds.

Basically, I built a compost pile in my greenhouse. Then as the compost pile heated up, I set my seed trays on top of it. The heated compost pile became my seed mat. I thought I was so clever!

Later, I learned that the idea of using some protected area like a greenhouse or cold frame and making compost in it to increase the heat in your gardening area is a very old idea – like pre-electricity old. It’s even got a name. It’s called a hotbed.

An Oldie But Hottie: Hotbed Gardening

If you were gardening pre-electricity, in cold weather, this idea of hotbed gardening would be about as ordinary as line-drying laundry. Now, though, we tend to overlook the simplest ideas and go straight to some complicated, electricity-based technology solution instead.

Thankfully, it doesn’t have to be that way. At least not when it comes to getting a jump on your growing season while it’s still cold outside. If you want to get back to the basics and garden in cold weather using an “oldie but goodie” gardening trick, then read on to make hotbeds on your homestead.

Hotbed Basics

All hotbeds require two things. The first is protection. The second is a proper compost pile.

Requirement No. 1: Season Extension Space

First off, you need some sort of protected area such as a greenhouse, hoop house, cold frame, walipini, or another season extension-type space. Any season extender that keeps out wind lets in full sun, and prevents frost from setting in can work.

Other than meeting those basic requirements related to wind, sun, and frost, your season extension space needs to be compatible for a compost pile to go on top of, or inside of, and still have enough room to grow your plants in soil.

You also need to be able to cool your season extension space by opening windows or lifting lids. Depending on how much your climate fluctuates, you may also want your season extension space to have easy access to water for emergency bed cooling.

Here are some examples of different season extension spaces and how to use them for hotbeds.

– Greenhouse, Hoop House, Walk-in Walipini

If you build your hotbed in a greenhouse, hoop house, or walk-in walapini, you’ll likely have plenty of room for a good-sized compost pile. So, this is a great place to make your hotbeds.

Situating your hotbed under your windows or near to your doorways can allow you more control to cool your hotbed down with air circulation if necessary.

– Cold Frames

If you want to use a cold frame, you have a few different options.

- You can make a cold frame that is deep and large enough to have the compost pile in the cold frame. This basically turns out to be like a 3-4 foot tall raised bed with a cold frame lid.

- You can dig a pit in the ground that is about 2-3 feet deep to make your compost pile in the pit. Then you can set your cold frame and plants on top of the pit.

- You can build a compost pile that is at least a 6 to 12 inches wider on all sides than your cold frame. Then, you place your cold frame on top of your pile and plant inside as you would if it were on the ground.

Requirement No. 2: Compost Pile

Making a compost pile for a hotbed is very similar to building a compost pile for the purposes of making compost. It requires the same basic ingredients and skills to make.

If this is your first time composting, you may want to do a little background reading so you know the basics of composting.

– Carbon to Nitrogen Ratios

For best results in your hotbed, you need to aim for a compost pile that contains 25-40 parts carbon to one part nitrogen. Using materials that add up to this range of carbon to nitrogen will ensure that the bed heats up.

– Greens and Browns

Some people also think of this in terms of greens and browns. In general, greens are things that have less than 30 parts carbon to each 1 part nitrogen. Browns are things that have 30 or more parts carbon for each 1 part nitrogen.

Some examples of greens are fresh chicken manure with no litter (7C:1N), kitchen scraps (15C:1N), and grass clippings (10C:1N). Some examples of browns are shredded paper (180C:1N), mulched leaves (35C:1N), and straw (80C:1N).

When you mix these in a manner that adds up to the right ratio, you get a hot compost pile. Often using 1 part green to 2-3 parts browns will usually get you in the right range for making hotbeds.

This is particularly true if you are using ingredients like cut grass and kitchen scraps as your greens and leaf mulch and paper products as your browns.

– Using Livestock Litter

Litter from your chicken coop is often perfect for making a compost pile. When you have roughly 1 part chicken poop to 2-3 parts straw, you naturally fall into the proper range for composting.

Litter from goat or horse barns also works well. Even though those sources of manure have less nitrogen than chicken manure, that littler also contains urine. It also usually has straw and hay to balance out the manure and urea.

Fresh cow manure layered with straw also works well. Cow manure has about 20 parts carbon to 1 part nitrogen. So just by alternating a few inches of cow manure with 1-2 inches of straw will end up in the right range for a hot compost pile.

– Pile Size

For a normal hot compost pile, you would use the carbon to nitrogen ratios described above and make your pile at least four feet tall and wide. That pile would get up to about 135-145°F within a few days. Then it would stay that hot for quite some time since the pile is so big.

With a hotbed, that temperature would be a bit too hot for planting and would take too long to reduce. So, instead, we build our pile to about 2-3 feet tall.

If you are composting in a pit, with no wind disturbance and a close-fitting cold frame on top, a 2-foot pile is enough. If you are open-air composting, such as in a greenhouse or setting a cold frame on top of your pile, a 3-foot tall pile that is about four feet wide, or wider, works better.

When to Use Hotbeds

Generally, I use hotbeds about four weeks before my last frost to get a jump on the season. Most of the heat from the composting process will disperse by that point. You’ll still get some residual warmth for a few weeks after that. But, it’s not generally enough to withstand extended cool weather.

I have read that some people use hotbeds for up to 2 months. In cold climates where people grow cold-hardy crops using hotbeds, that can work. Cool season crops will develop good root systems in that two month period.

Once established, just the cold frame is sufficient for continued growth. A hotbed base is no longer necessary.

Remember that plant growth is always dependent on light and not just temperatures. As such, hotbeds don’t have as much utility for fall or winter planting when day length is diminishing. They are most useful when day length is increasing such as in late winter or spring.

5 Steps for Making Hotbeds

Now that you know the basic requirements, making the hotbed is really simple.

1. Build Your Compost Pile

You need to add your browns and greens all at once. Layer your browns between your greens to create airflow. If you are using litter, make sure you pull apart any hardened clumps or soggy areas as you build the pile.

Water as needed between layers. Your goal is to saturate your compost materials with water, similar to a damp sponge, but not soppy. Things like kitchen scraps tend to have lots of moisture. So if your kitchen scraps are a mushy mess, then you may not need to water layers that include them quite as much.

2. Cover Your Pile

Now you need to make sure your compost pile doesn’t get rained on. If you built it in a greenhouse, make sure to close your windows when it rains heavily. If you built it outside, you could cover it with your cold frame or a tarp until it’s ready to use.

3. Wait for Things to Heat Up

In a few days, the pile will start to get hot. If you’ve got the right carbon to nitrogen ratios, and built it to a suitable height, it should get to 90 – 105°F quickly. Use a compost or soil thermometer to check your temperature.

The outer edges of the pile will be a bit cooler. Also, sometimes there are hot spots in the pile. So, personally, after I check the bed area with a thermometer, if it’s in range, I then use my wrist to gauge the readiness of the pile on the surface.

It should feel like a warm, sunny day in late spring or early summer. If I can’t leave my wrist on the bed comfortably, then it needs a few days to cool.

4. Use Your Hotbed

At this point, you are ready to use your hotbed for planting. If using a cold frame, now is the time to put it on. In stand up structures, you are clear for take-off!

There are basically two ways of using a hotbed. It works well for starting seeds in containers or direct planting when topped with soil.

Option 1: Seed Starting

You can set your seed starting containers right on top of the pile and use it as a heating mat. This is what I use it for.

I set paper feed bags on top of the pile to create a more uniformly level surface. They also soak up some of the water before it enters the pile to help keep temperature high. Then I put my containers on top of that bag layer.

Option 2: Planting Area

You can also add 4-6 inches of soil mix or sifted compost on top of your compost bed. Then you can plant seeds directly in it.

The soil will act as a filter to limit the excess water used on your seedlings from reaching the compost bed below. Similar to using paper bags under seed trays in option one, this keeps the compost from getting too moist each time you water newly planted seeds.

Note – you don’t want to transplant seedlings started indoors into your hotbed until the compost pile temperature has dropped to below 75°F. Otherwise, the roots will get too warm.

By starting seeds in the hotbed, you allow the compost pile temperature to drop as the roots are growing down. When the roots reach the hot zone, the heat source has already cooled quite a bit.

5. Monitor Your Hotbed

There’s no temperature control dial on your compost-based hotbed. Environmental conditions like your outdoor air temperature, the way you layered your pile, how much water reaches the interior, and more can all cause temperature fluctuations.

– Adjust for Environmental Factors

You will need to open and close doors, windows, and cold frame covers quite regularly to keep your hotbed cool on warm days or when it’s sunny. You will also need to water occasionally to make sure the bed keeps the consistency of a moist sponge.

– Unexpected Cold

If your temperatures turn unexpectedly cold, you may also need to insulate your hotbed to save your early started plants. You can surround it with straw bales or cover it with a heavy duty blanket. You can also mulch around it with leaves or insulate with tightly piled cordwood.

– Level the Bed Area

Your hotbed will also shrink as it composts. So, your planting area shape may change. This doesn’t always happen uniformly.

The compost pile may slope or have divots. You may need to top off any low areas of the bed with some finished compost or soil to keep it level.

Hotbed Greens Garden

If you want to take hotbeds to the next level, consider making a hotbed garden. Basically, you cover a garden area with a giant compost pile. Then you cover the sections you want to plant with 4-6 inches of soil or sifted compost. This works well if you have lots of livestock litter from your winter deep-bedding.

You can then use floating row covers or cold frames over the bed area to reduce wind and keep frost from settling. Or if you want to go really big, you can use hotbeds inside high tunnels.

I use this concept to get a jump on all my cut greens like kale, lettuce, mustard, arugula, bok choy, spinach, Chinese cabbage, etc. They are all somewhat cold hardy in the first place. So, they don’t need a lot of cold weather protection.

Still, the hotbed raises soil temperatures for faster germination. It also speeds up growing times by providing more consistent warmth. Finally, because plants are already adapted to warmer soil temperatures, they are less likely to bolt at the first warm day in spring.

Conclusion

Even though hotbeds are an old idea, they are new to many of us. Getting the hang of using them is a skill we have to develop. It takes a little bit of practice to get your temperatures regulated and your timing right.

I encourage you to consider your first time or two of using a hotbed to be an experiment. Continue to plant using your normal methods as a backup.

Starting seeds in hotbeds, rather than direct planting, is also easier at the outset. That way if your hotbed gets too hot, you can move containers to another location until it cools down.

After a little practice though, using hotbeds will become as natural as line-drying laundry is to all of us hardcore homesteaders.