Homesteading is full of opportunities to learn new skills. From canning to homemade cheese and wine, there’s always a chance to do a little more at home. When it comes to winemaking, it often starts with an overabundance of something in the garden.

For us, that overabundance was rhubarb. Overwhelmed with rhubarb stalks, we quickly learned that rhubarb wine is a tasty way to use up our extra stalks.

Once we started making rhubarb wine, we discovered all kinds of other “garden wines.” Homemade wines are easy to make, and they add a unique flavor to your homestead meals and celebrations. They also make ideal gifts.

Getting Started

There is a host of at-home wine-making products on the market. If you want to, you can spend thousands of dollars setting up your wine cellar. But don’t worry, most homestead winemakers make do with very few supplies.

Remember, people have successfully made their own homemade wine for thousands of years. Long before there were specialty carboys and airlocks, there were housewives brewing up batches of elderberry wine in old crocks.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with buying modern equipment if it’s within your budget. But don’t limit yourself. Go ahead and get started with whatever you have on hand.

1. Essential Equipment

You will need some sort of large container to hold the wine as it’s fermenting. Some people use beautiful glass jugs called carboys. These beauties make your fermenting wine into home decor throughout the fermentation process, but they can get pricey. Some people simply use food-safe 5-gallon buckets.

At our house, we use fermentation crocks for the first fermentation stage. Then we transfer the wine into clean, used bottles for the second fermentation.

Airlocks are another item that is helpful to have on hand. You can make wine without using airlocks, but it can be challenging. Fortunately, airlocks are pretty inexpensive. The point of an airlock is to allow the wine to ferment in a closed environment without letting the pressure build (fermentation produces gasses).

A siphon is the last, basic tool you’ll need. The siphon will allow you to gently transfer your wine from one fermentation area to another without bringing all the sediment along with it. Siphons are usually very simple and inexpensive.

2. Necessary Ingredients

Ok, now for the ingredients themselves. First and foremost, you need some sort of juice or tea to make your homemade wine. Grape juice from crushed grapes is obviously one option, but don’t limit yourself.

Strawberry, elderberry, pear, apple, and rhubarb are all great options. I’ve also made wine from dandelions and bee balm.

You’ll need yeast, but baking yeast is not the best option. Choose one of the many wine-making yeasts instead. These yeasts are cultured to work well in wine-making and avoid the off-flavor that baking yeast can bring to the mix. There is a variety of wine-making yeasts available at most natural food stores and online.

The yeast will need some sugar to feed off of during the fermentation process. If you’re making grape or strawberry wine, you may not need to any much, if any, extra sugar to the mix. But if you’re working with something without many natural sugars, you’ll definitely need to add some of your own.

Filtered or untreated water is another essential. Use untreated well water, spring water, or rainwater rather than unfiltered tap water. Depending on your town’s treatment plan for water, the water from your tap may contain high levels of chlorine, fluoride, or other chemicals that can kill the yeast.

Making the Wine

Start by sanitizing your carboy or bucket. You can purchase special sanitizing tabs, but it’s just as effective to wash the container in hot, soapy water and then rinse it with hot water.

Then, just add all your ingredients to the container. You’ll have to crush the fruit to release the juices or make a strong tea with the dandelion blossoms. Then add the juice or tea to the container. Add in yeast and sugar (if necessary).

Since not all juices need added sugar, some people like to use a tool called a hydrometer to measure sugar levels. But, since it’s a good idea to work from a recipe in your first few batches of wine, you may not need one immediately. Your recipe will tell you whether to add sugar and how much.

Once all the ingredients are added together, leave it alone to begin working. Wine ferments best at about 70-74°F, which is an easy temperature to maintain in the summer but might take a little work in the fall and winter.

Within 12 hours, you should start to see the yeast working in the wine mixture. You’ll notice tiny bubbles starting to form and rise to the top. Now you’re well on your way to enjoying your homemade wine.

Let this mixture work for about a week or two. Each recipe is slightly different, keep an eye on the recommended times for your specific ingredients.

Straining

After the initial fermentation, you’ll need to strain out some of the sediment. You can use your siphon, especially if you’re moving the wine from one heavy container to another.

But, if you don’t have a lot of sediment, you can simply skim off the froth and leave your wine in the large container until it’s time to rack.

Alternately, if you have a narrow-mouthed carboy or an easy-to-handle jug, you can pour the wine through a strainer to remove the sediment and froth from the fermenting mixture.

Your homemade wine now continues to ferment for another three weeks to two months.

Siphoning and Racking

After that long fermentation, you have real wine! It’s not quite ready to drink yet, though. At this stage, the wine is still very fresh and sweet – not all the sugar has been converted to alcohol yet. It’s time to rack the wine and set it on the shelf to age for a while.

Use your siphon to move the wine to another carboy or into bottles. If there’s a lot of sediment at the bottom of your fermenting container, you may want to siphon the wine twice. Rack it into a fresh carboy, clean out the old one, and then rack it back into the newly cleaned carboy.

You can continue to rack and rack back your homemade wine every month or two until most of the sediment is gone, or you can let the wine rest after the first racking. This is your wine, after all!

Whether you’ve racked your wine into a carboy, or into a collection of old bottles, you’ll need to find a way to airlock it. If you cork wine this early in the fermentation process, the gasses will simply pop the cork out again when they build up too much. Since airlocks aren’t expensive, it’s relatively simple to siphon into bottles and then fit each one with an airlock lid.

Bottling and Corking

Now, that your wine is racked, it can rest for a few months, or almost a year. But eventually, it’ll be time to cork the wine into bottles. If your wine is racked in bottles and you don’t want to rack it again, you simply switch out the airlock lid for a cork. If your wine is racked into a carboy or large container, you’ll have to siphon it into clean bottles.

As your filling bottles, make sure to leave about a half inch of head space as well as the space you’ll need for your cork. Insert the corks into the bottles. Then store your wine bottles upright for the first 3-4 days (just in case there were more fermentation gasses than you realized). After that, you can seal the corks with wax if you want to and store the bottles on their sides.

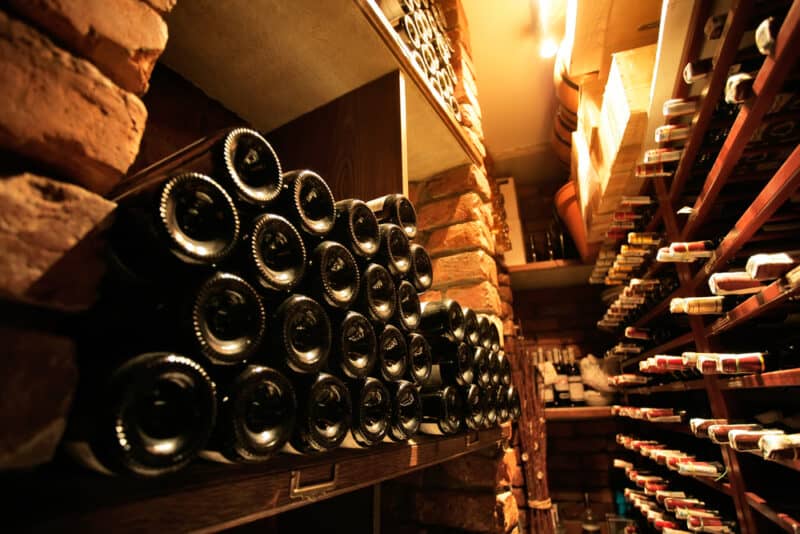

At this point, the ideal temperature for storing your wine is about 55°F. Tuck these bottles in the basement or wine cellar and let them mature.

Maturation

Every wine is different, especially when it comes to maturation. If you’re making grape wines, red wines generally need at least a year to mature from corking to drinking. Most white wines need only about six months.

Elderberry wine usually needs about a year to mature as well. Rhubarb wine only needs 5-6 months but becomes much more mellow after about eight months.

Each recipe will have advice as to how long the wine should mature. But I like to cork a few small bottles to try out my own timing. Cork one to open at six months, one at eight months, one at a year, and one at a year and a half to explore what time does to the flavor of your homestead wine.