Most homesteaders can easily spot the signs of powdery mildew in their garden. The tell-tale signs of a powdered sugar looking substance on the tops of plant leaves is hard to miss. Downy mildew though is a bit less obvious.

Downy mildew lurks on the underside of plants. Many gardeners don’t even notice it until the algal-like pathogen has already starved leaves of water and nutrients. Unfortunately, when the leaves show that grainy, desiccated appearance that indicate advanced downy mildew, it’s too late to treat effectively. That’s why prevention and early detection are key tools in the battle against downy mildew.

About Downy Mildew

Most of us gardeners think of downy mildew as a fungal pathogen. However, it actually operates more like algae. From a scientific perspective, it’s called an oomycete. It’s treated as something of a hybrid because it’s algae-like in its biology but fungicides are somewhat effective in its treatment.

Regardless of whether you rate it as a fungal pathogen or a parasitic algae, it can be a big problem for your plants. In temperatures between 50-70ºF, it swims through water in the soil to reach suitable plant hosts. Then, when it rains, or you water your plants, downy mildew bounces up in drops of water to the underside of your plant.

From there, it begins to parasitize your plant leaves by sucking out water and nutrients. Like an algal bloom, it expands across more of the leaf surface. Wind, rain, and watering move it from leaf to leaf until your entire plant begins to show signs of chlorosis (lack of nutrients) and struggles to survive.

It’s not a pretty picture when your plants succumb to downy mildew. Crispy leaves, unripened or rotting fruit, and increased insect attacks are all part and parcel of being colonized by this fungal-like algae-ish pathogen. Fortunately, there are some things you can do to limit your risks and control the impacts of downy mildew in your garden.

Downy Mildew Identification

As I mentioned at the outset of this post, downy mildew is usually only noticed when it has already done severe damage to your plants. However, if you know what to look for it, it’s easy to spot early.

Early Signs

A spot, in fact, is the exact thing you are looking for. Downy mildew most often looks like an oil spot on leaves when it begins. As it advances, it takes on a downy appearance on the underside of leaves that’s been described as cottony. That down can then turn from whitish to darker colored, tending toward grayish-black.

Late Signs

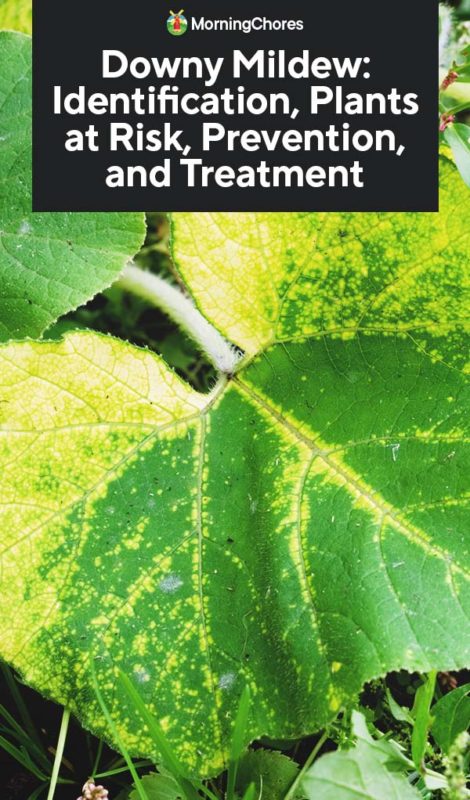

The late effects of downy mildew on the tops of leaves are often what most gardeners notice first. It usually starts as yellow spots near the veining of plants. Then, it expands out along all the central veining of your leaves and looks a lot like nitrogen chlorosis.

Final Signs

After that, the leaves can take on a grainy appearance as they begin to dry out. The edges will curl. Suddenly, your leaves look like crunchy potato chips. Unfortunately, when it gets to this stage, it’s usually not just one leaf, but much of the plant that’s deep-fried.

Unless your fruits are nearly ready to harvest when you get to this advanced stage of infestation, you might be in trouble. Once downy mildew takes over, your plants likely won’t have the leaf capacity to gather enough sunshine to photosynthesize the nutrients needed to finish the job of growing fruits to maturity.

This pathogen usually doesn’t kill your plants entirely. But it can dramatically reduce productivity and make getting a harvest impossible.

Plants at Risk

Downy mildew is what we call an obligate parasite. That’s a fun phrase to describe the fact that this plant-life-sucker is host-specific. So, the same downy mildew that’s on your sunflowers can’t jump to your cucumbers. However, there are about 600 known types of downy mildew, many of which can infect a wide range of plants including fruits, vegetables, and ornamental plants.

For homesteaders, here are the plants you’ll want to keep a close eye on:

– Cucurbits

Any plants in the cucurbit family are at risk for downy mildew. This includes all your cucumbers, squash, watermelon, cantaloupe, pumpkins and more. These plants seem to be quite susceptible to downy mildew in areas that are already excessively humid (e.g. where I live in North Carolina).

– Basil

That lovely sweet basil you grow to pair with your tomatoes and fresh-homemade mozzarella is highly at risk for downy mildew if you try to grow it in cool moist conditions. The good news is that basil likes hot weather, so if you just wait until a bit later to plant basil, you can reduce your risks.

– Grapes

Downy mildew in grapes is rampant. It spread from the US to France back in the late 1800s and then across Europe to the rest of the world.

Now vineyard managers everywhere diligently take every precaution to avoid it. Worldwide, there is only one remote region in South Africa where downy mildew is not completely rampant in vineyards. Otherwise, all grapes are at risk.

It’s also not just the leaves that are impacted. The fruit can host downy mildew too, often making it unusable.

– Sunflowers

Sunflowers, which make both a beautiful and tasty addition to any homestead, are subject to downy mildew. Again, similar to basil, since sunflowers love hot weather, planting them when the soil stays above 70ºF can cut down risks.

– Lettuce

Lettuce, like sunflowers its close relative, are also susceptible to this pathogen. Because lettuce grows close to the soil, it can be hard to prevent infections. Planting downy mildew resistant lettuce cultivars can help.

– Legumes

Soybeans are highly susceptible to downy mildew. Thankfully though, soybeans tend to be able to tolerate infestations better than other plants.

Snap beans may also be a host for the same downy mildew pathogen that infects soybeans. Peas too may be at risk. However, the extent to which these plants are bothered varies wildly by variety grown.

– Spinach

Spinach is a perfect host for downy mildew. Organic growers worldwide have had issues managing downy mildew in spinach because organic fungicides have limited efficacy as a treatment. Also, spinach requires cool moist conditions to grow well which are also ideal for downy mildew development.

– Ornamental Plants

A number of ornamental plants are also at risk for downy mildew. Impatiens are the most notable example because downy mildew has had large economic impacts on the nurseries that grow them. Roses too are at risk. Even though downy mildew may not kill ornamental plants, it does make them aesthetically unappealing.

– Hops

Unless you are a beer maker or make herbal medicines, this last downy mildew victim might not impact you. But, just in case you are growing hops, downy mildew is the second biggest killer of young hops plants. Hops require lots of moisture to grow well which, unfortunately, makes them a perfect target for water-loving downy mildew.

– Other Plants

Quite frankly, there are a lot of other plants that are beginning to be at risk for downy mildew. Tobacco, blackberries, sweet corn, and lots more plants also have some risk for downy mildew. More variations of these pathogens are being studied and documented regularly.

The Life Cycle of Downy Mildew

Similar to fungal pathogens, downy mildew is spread by spores. The spores can be transmitted by water splashing off the soil and hitting leaf parts or be carried on the wind.

When they come into contact with a suitable host plant, they attach to the leaves and begin to reproduce. Damp, cool conditions then help the spores spread quickly.

Suckers

The spores attach mainly to the tender undersides of leaves that are more delicate and porous than tops. There, in the protection of shade, a few spores can quickly colonize the entire leaf and bounce to other leaves in splashes of water or on breezes.

Because the spores have to live by feeding on specific plant hosts, when the leaves eventually succumb to being eaten alive by algae, many of the spores die too. However, this pathogen has a survival trick. It produces oospores that can hibernate until conditions are right for growth.

Oospores

The oospores fall to the soil in the dried leaves, move in, and wait for the right conditions to infect new plants. Sources say they can remain dormant for up to 5 years, in some rare cases even longer.

The good news is, even these dormant spores, don’t tolerate cold weather well. So, most of the oospore outbreaks are in warm climate areas or greenhouses. Climates with extended freezing conditions have a bit of natural protection from extended infestations.

Vectors of Transmission

This pathogen can spread by wind transmission over short distances. It can also spread by planting infected seeds or plants. The infected plants then pass this pathogen on to other plants through water or wind transmission. Gardeners can also play a role in transmitting spores from one plant to another on tools.

Prevention Steps

Now that I’ve told you all the bad news about this ooey, gooey oospore making oomycete, let me give you some good news.

It can be controlled using good gardening practices.

1. Crop Rotation

With downy mildew, crop rotation is key to cutting down risks for re-infection. If you have an outbreak on your lettuce one year, then take a 5 year break before planting lettuce there again in warm climates. Or take a year off in cold climates.

2. Remove Infected Leaves or Plants

Carefully remove any leaves infected with downy mildew early to reduce risk of transmission to other leaves and plants. In the case of severe downy mildew, consider removing the entire plant.

Burn the infected plant material. Or, allow it to roast in 95ºF temperatures, such as under black plastic, for 6-9 hours before adding it to your hot compost pile.

3. Water Right

By watering the soil, rather than the plant, in the morning when temperatures are rising, you reduce the risk for the pathogen splashing onto leaves. Also, if it does, then the leaves will dry quickly in sunlight and the spores may not get a chance to grow before they dry out.

4. Plant in Warm Weather

These oomycetes do most of their sporulating at temperatures between 50-60ºF. Heat loving plants like basil and sunflower can be started in warmer weather to avoid peak sporulation.

5. Mulch

Mulching under plants with things like compost, straw, wood chips, or leaf mold can cut down the risk that spores will splash up onto plants. That will also preserve moisture in the soil and cut down how frequently you have to water during peak sporulation temperatures.

6. Stake and Prune

For some plants, like grapevines or hops, you can limit your risk by growing them vertically. You can also prune leaves at the lower levels to limit soil splashing and upwards transmission

Hops are generally grown on lines that reach up 10-20 feet. Grapevines can start as low as 2 feet from the ground. But many growers have started raising the first trellis line to cut down on the risk for downy mildew. Roses too can be trained to grow well off the ground for greater downy mildew resistance.

7. Avoid Monocultures

In my vineyard, with the vines of one plant practically touching the vines of the next, I have to battle downy mildew in my hot, humid climate which receives heavy spring rains. However, I also have grape vines interplanted in my vegetable garden, around my fruit trees, lining my lawn and more.

Those individual plants, mixed with other plants, never get downy mildew even though they are equally susceptible. Because these tiny spores must swim slowly through soil, splash, or catch the wind to spread, there’s a limit to how far they can go. Also, since they don’t get to pick which plant they land on if you put a few non-host plants between hosts, they are more likely to land on those plants they can’t harm.

8. Resistant Plants

You can also buy resistant plants. Even though downy mildew has been around in some plants since the late 1800s, there aren’t very many resistant cultivars yet. However, as temperatures warm up around the world and some places have fewer hard winters, the need for disease-resistant cultivars has dramatically increased.

As such, many plant growers have started working to develop downy mildew resistant options in all sorts of plants. You can now find downy mildew resistant sweet basil, lettuce, roses, and more.

Unfortunately, there are no known grape vines that have proven resistance to downy mildew. However, muscadine grapes, such as the Noble variety, do seem to have greater natural resistance when grown using the other preventative tools outlined above.

9. Preventative Fungicide

I am not a fan of fungicides. Even when you use targeted fungicides for certain plants, the sprays tend to impact the beneficial fungi as well as the pests. However, if you are trying to grow grapevines in a Southern climate, you may have no other choice than to suppress downy mildew spores.

If you must commit fungicide, opt for targeted fungicides rated for use against downy mildew. Use them only when necessary and apply only as much as needed for effective results. Also, consider using some of the other methods above to limit your long-term need for fungicides.

Neem and copper are two organic solutions with some proven efficacy. However, both of these have their drawbacks. So study up before you spray.

10. Buyers Beware

Warm climate and hothouse plant growers are more likely to face challenges from downy mildew than people in cold climates because the oospores can overwinter and recur annually.

Buying outdoor grown, overwintered plants from northern areas can be safer than buying from say Florida or greenhouse growers anywhere.

Post-Infection Treatment

There are a few things you can do after an infection to slow the rate of progression or kill the spores.

11. Solarize

If you put plastic sheeting over your plants on a sunny day and raise the temperate around your leaves to 95°F for 6-9 hours, research shows you can kill the spores on the leaves. This is not going to be the best option for things like spinach and lettuce that like cooler temperatures. However, basil, sunflowers, and grapevines won’t mind terribly for a day or two.

12. Use a Fan

On a small scale, you can also run a fan to dry your plant leaves during an outbreak. This cuts down on transmission when coupled with plant grooming to remove infected leaves.

This is only practical if the rain comes at the wrong time and is followed by dry weather. So, for most homesteaders, it’s not realistic.

13. Skip the Fungicide

For downy mildew, fungicides are marginally effective once an outbreak starts. Also, this pathogen has shown an aptitude to become resistant to fungicide quickly.

As such, don’t bother using a post-infection fungicide and avoid making a bad situation now a nightmare in the future. Just like antibiotic resistance – the more you spray now, the fewer options you’ll have to work with down the road.

Down with Downy Mildew

Downy mildew doesn’t have to be a total downer as long as you do a little preventative work to protect your plants. Most of the things you can do for prevention like mulching, staking, interplanting, and growing resistant varieties, are just good practices to make gardening easy anyhow.

Just by being a good gardener, you can beat your downy mildew blues!

References

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?pid=683

- https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=9470

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0126103

- https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/oomycete/pdlessons/Pages/DownyMildewGrape.aspx

- https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/full/10.1094/PDIS-12-17-1968-FE

- https://awaytogarden.com/basil-pressure-fight-devastating-downy-mildew/

- https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/lettuce/downy-mildew/

- https://vegetablegrowersnews.com/news/downy-mildew-resistant-basil-varieties-now-available/