Nematodes often get a bad wrap on our homesteads. We worry about root-knot nematodes ruining our tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, okra, peas, and more. Those sneaky little critters attach to our plant roots, inject them with a serum that causes galling, and then sit back and watch as a host of other bad stuff like fungal pathogens or bacterial diseases destroy our plants.

Of course, we all also worry about intestinal nematodes like what we commonly refer to as roundworms or hookworms. These intestinal parasites are one of the big reasons why many pet owners are reluctant to compost dog poop even though there are some easy ways to make that process safe.

Nematodes are also the reason why good goat herd managers are always on alert to manage parasite overload early. The potentially lethal barber pole worm often evidenced first by signs of anemia, is another perfect example of why nematodes get a bad wrap.

Nematodes though, like fungi, are also essential and beneficial to our gardens and ecosystems. They do immense amounts of important work. Without their contributions, we might have some serious problems producing food or growing any kind of plant.

What are Nematodes?

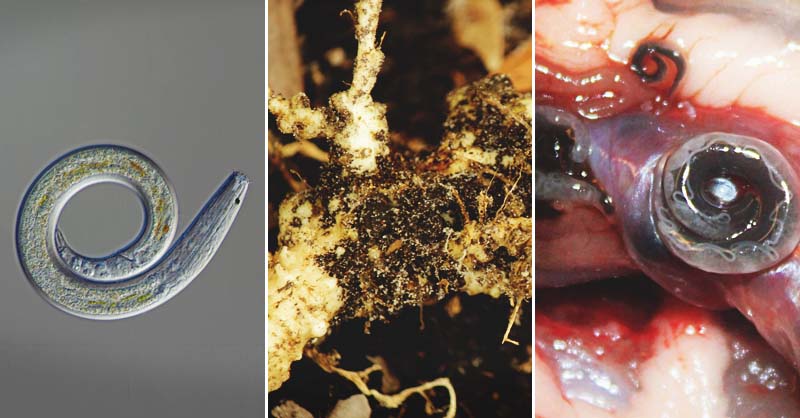

Bob Goldstein, UNC-Chapel Hill

‘Nematode’ is a generic name for all the tiny unsegmented worm-like creatures in the phylum Nematoda. These critters also fall broadly into the category of insects even though some are so small, you’ll never notice them.

Nematode Population

A recent study determined that there are roughly 57 billion nematodes for every single human being on earth. That makes them the most numerous animal phylum on earth.

Nematode Size

They can range in size from microscopic to over 3 feet long for some intestinal parasite nematodes. If you add up the weight of all those minuscule and monstrous-seeming nematodes, they weigh in at about 80% the mass of all of us humans.

Nematodes Are Everywhere

Even though you may not have realized it, nematodes are all around you. They inhabit nearly every surface and water body on earth from the ocean floor to the mountain tops, from the depths of the soil to the tops of the trees. Every time you dig in the soil or spread compost without gloves, you are practically swimming in them.

Are Nematodes Bad?

Don’t panic though! Those huge population figures I just detailed tells us that all nematodes can’t be bad; even though we only think about nematodes when they kill our tomatoes or our goat needs a de-wormer. If they were all bad, and they outnumber us by 57 billion to 1, we’d be in some serious trouble!

The fact is that when it comes to understanding nematodes most of the research out there is focused on the small number of nematodes that negatively impact agriculture and human health. Scientists are only just beginning to understand the complex (and mostly beneficial) role all those other nematodes play in our environment.

Nematodes in the Soil

Up to 90% of nematodes may live in the top 6 inches of the earth’s crust. Large populations of these little worm-like creatures likely also live in the low fertility, slow decomposition soil and water systems of the Arctic. Yet, they are also present in large numbers in both organic and conventionally managed soil everywhere.

In the soil, nematodes perform various functions. They make minerals available to plants, control fungi and bacteria populations and kill some pests. However, those we worry about most tend to be plant-eaters that ruin our crops.

Carnivorous Nematodes

Some kinds of nematodes also help manage potential fungal, bacterial, and insect problems by eating those pathogens, thereby reducing their populations. They may also play a role in helping to modulate the turnover rate of nutrients in the soil by keeping even beneficial bacteria and fungi populations at a sustainable rate.

Quite frankly, scientists simply don’t know enough about nematodes yet to suggest strategies for encouraging the good guys and managing the bad nematodes in our soil. What we do know is that soils with larger populations of nematodes correlate to more carbon storage.

As such, some scientists are scrambling to understand how fluctuations in temperature and rain events will impact diverse nematode populations in our soil. Here are a couple of recent findings.

Heat-Loving Nematodes

When soil temperature goes up in a monocrop field (e.g. only one crop), nematode diversity goes down. When soil temperature goes up in a diversely planted field (e.g. 16 different crops), nematode diversity goes up. What we don’t know yet is whether those heat-loving nematodes in diversely planted fields are beneficial or not.

Generally, diversity in eco-systems tends to be a good thing. So, people interpreting these research results are taking this as a mandate to diversify crops by interplanting and poly cropping to help mitigate risks from climate change.

Cannibal Nematodes

Some nematodes are also cannibals and will eat other nematodes in their phylum. For example, some predator nematodes feed on root-eating nematodes.

In a study conducted in grasslands, hot dry conditions reduced the predator nematodes and allowed the root-eating nematodes to thrive. That, of course, leads to the idea that maintaining soil moisture levels is going to be key to keeping plants and soil healthy in hotter weather.

Nematodes as Pesticide

Scientists are also focusing on a number of beneficial nematodes that are able to naturally control some of the most costly pests in the garden. For example, recent scientific discoveries have isolated pheromones that can attract pest-eating nematodes to plants with pest problems. This is potentially great news for the pecan industry and it’s weevil problems or corn farmers with other insect issues.

Some nematodes also help boost the immune system of their host plants to make them less susceptible to bacterial and fungal infections. It may seem counter-intuitive. But if a parasitic nematode attacks a plant and the plant beefs up its defenses in response, the plant could then use those enhanced defense systems against a host of attacks.

The challenge is that even though nematodes set off early warning systems in plants, some are also really good at getting around them as they increase their population and infest plants. The old adage “whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” is an apt description for this delicate dance.

Harmful Nematodes

There are also a number of nematode pests that homesteaders who have gardens and raise livestock fear.

Plant-Eating Nematodes

Plant-eating nematodes such as root-knot nematodes, cereal cyst nematodes, root-lesion nematodes, stem nematodes and more. Though it is hard to see an outbreak of these nematodes as a good thing, the plants that survive due to natural resistance can lead to healthier future generations of plants.

You can now even buy seeds from plants that have demonstrated natural resistance to nematodes. Many of those nematode-resistant plants also show more resilience against fungal and bacterial pathogens too.

So, while dealing with a bunch of nematode-infected plants might suck, the long-term benefit is that the strong plants get identified and propagated and can help increase production in our gardens down the road.

Livestock Nematodes

If you have livestock or pets, you probably already know a fair bit about nematodes even if you call them by other names. Just as with gardens, we frequently focus on the not so beneficial nematodes in our scientific research.

Still, there is a positive breakthrough in our understanding of nematodes. For example, many of us goat keepers are beginning to understand that just like plants can resist nematode parasites, so can our livestock. If we breed bucks and does with natural parasite resistance together, their kids tend to have good resistance too. That means we can de-worm and worry less.

We’re also beginning to realize that some kinds of fodder, as part of a balanced diet, can help increase the resistance our livestock have to parasitic nematodes. For example, in goats, research suggests that adding the easy to grow lespedeza hay to our goats’ diets and pasture can make them less prone to infestations. The Birdsfoot trefoil legume may also offer similar benefits in cold climates.

Living with Nematodes

I’m barely scratching the surface of fascinating facts on nematodes in this post. With an estimated 30,000 kinds, living on every crevice and in every waterway on earth, it’s unlikely we’ll ever fully understand them.

What I do know as a gardener and livestock manager, though, is that nature is always about balance. Nematodes, even the bad guys, serve important natural functions.

I also know with total certainty that maintaining organic soils full of all sorts of micro life including diverse populations of nematodes is good for my garden. Plus, growing a greater diversity of plants, instead of monocrops, offers better pest control against nematodes and other pests.

One thing is sure, nematodes are a necessary part of a working ecosystem. We may not always appreciate their contributions. Yet, without them, the incredible natural diversity of plants and animal life we take for granted today could not exist.

Other Beneficial Uses

Just in case you are still not convinced that nematodes deserve a place of respect in your garden, let me leave you with one more exciting development. There is a kind of nematode that infects slugs and snails. It then controls their behavior, effectively making slug and snail zombies.

Researchers have recently determined that by mimicking the effects of these nematodes, infected slugs and snails could be directed to move en masse to certain areas – such as far, far away from our gardens.

Famed permaculture founder Bill Mollison once said you don’t have a slug problem, you have a duck deficiency. Well, in the future, gardeners everywhere might be saying you don’t have a slug problem you have a Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita nematode deficiency. (Perhaps we need to shorten that to something like Phasmatode to make it a bit catchier.)