As the author of the book Grow Your Own Spices, one of the questions I am often asked is “what’s the difference between herbs and spices?”

From a cook’s perspective, there are a lot of right answers to this question. We could probably spend an afternoon debating the finer points – and have a great time doing it! However, from a gardening perspective, there is a clear answer.

Herbs are the tender green leafy parts harvested from immature plants, used for culinary flavor or aroma. Spices, by contrast, are any parts of a mature plant harvested for culinary flavor enhancement and aromatic purposes.

Here’s why the distinction between herbs vs. spices matters in gardening.

Spices vs. Herbs

Herbs are quite straightforward to grow. You need to know the basics of when to plant and how to care for herbs. You also need to understand how to harvest tender leaves without taking too much so you don’t kill the plant. Still, that’s about the extent of what you need to know to grow herbs.

For spices, you must understand the same basic care requirements as are required to grow herbs. However, then you also need to know a whole lot about things like pollination, flowering, planting to time harvests in accordance to day length and soil temperature, senescence, nuanced specifics on when to harvest, curing, and more.

Also, for beginners, growing herbs is a wonderful low commitment way to get your feet wet by gardening. So, if you don’t have a lot of time to spend gardening and aren’t entirely sure if you are going to love it, then starting with herbs is ideal.

Spices are a longer-term commitment which means there’s more risk for things to go wrong. However, they are also the most wonderful teachers of advanced gardening skills if you really try to understand what they need as you raise them to maturity.

Growing and harvesting spices from mature plants can help you delve deeper into plant lifecycles to further hone your gardening expertise.

Let’s look at an example.

Cilantro/Coriander for Herbs

In the US, we call the young leafy greens from Coriandrum sativum cilantro. These plants are easy to grow in the ground or in containers, indoors or out, and in full sun to part shade. They only need about a square foot of space and 4-6-inches deep compost-rich soil to have good leaf growth in the ground and allow for repeat harvests.

The seeds germinate in just a few days. With regular watering and full sun, you can begin harvesting the leaves in just over a month. You can even grow these as microgreens for a super quick harvest.

Coriander for Spice

Coriander, or coriander seed, is what we call the dried fruits of this same plant we grow for the leaves. When grown for spice vs. herbs, this plant needs soil that is preferably 8-12-inches deep for peak production. That’s because it forms a deep taproot to plump and holds up top-heavy seed pods as they form and dry on the plant.

Ideally, you should also grow several plants in a patch, but preferably more like 15-20 plants for great cross-pollination. If you grow these plants in cool weather and prevent early bolting, it will be about 3 months before they flower and sets green fruits. Then it will take another month for the fruits to mature and dry sufficiently for harvest.

1. Water and Fertilizer

You’ll need to water those spice plants regularly right up to flowering if you live in a dry climate. You may also have to fertilize your coriander plants with some compost tea, or side-dress with organic fertilizer if they appear stunted.

2. Flowering

Once plants elongate and flower, then you’ll have to keep an eye on them and make sure plenty of pollinators are visiting those plants every day. Coriander is dependent on pollinators for seed production.

If your flowers form when temperatures are between 68-80°F pollinators should show up in droves to pollinate your coriander for you. However, if it’s cooler or warmer than this ideal range, your harvest may suffer from a lack of pollination.

In hot conditions, you can put up an open-sided shade tent and offer a shallow dish of water with rocks inside to invite insects to visit and cool off while pollinating your coriander.

In cooler conditions, you can increase your chances of attracting the brave few pollinators out in the cold by planting coriander in large groups near other flowering plants to offer an attractive feast.

Also, keep an eye out for swallowtail butterfly larva. They will devour your coriander as it begins to flower if you don’t offer them their preferred flowering alternatives such as dill or fennel.

3. Harvest

After plants set fruit, then you need to wait until they are mostly dry, but not fully dry to harvest the seed heads. If you wait too long, the seed heads will shatter and self-sow in your garden. If you leave the heads out during several days of rain when they are partly dry, they may mold.

Choosing the perfect time to harvest coriander for spice is a bit of a dance between ideal dryness and ideal weather conditions. When you find the right time, then cut the entire seed head from the plant. Set them gently in a paper bag and let them finish drying in the bag. Finally, thresh, winnow, and store.

Spice Gardening

Now, don’t let all these details scare you off! Growing coriander for spice vs. for herbs is still quite simple if you just get your timing right for planting and have a little good luck on the weather front. However, it’s a great example of why spice gardening is significantly more involved vs. herb gardening.

I bet you can see from this one example how becoming skilled at growing spices can help you really hone and fine-tune your gardening skills. So, if you are ready to grow spices and your gardening skills, then let me share some of the many things you’ll learn about plants as you engage in that process.

1. Pollination

Spices grown for seeds or fruits require proper pollination. However, the exact kind of pollination required varies by spice.

– Self-fertile

Some spice plants are completely self-fertile. For example, fenugreek will produce seeds even if you only grow one plant at a time. Piper nigrum, the plant that produces black, red, and white peppercorns is also completely self-fertile and will even have production in a greenhouse or indoor garden setting.

Yet, there are other spices that are self-fertile but prefer cross-pollination. Mustard is one of those plants that can produce seeds even if you only grow one plant. With mustard, though, your seed yields will be dramatically increased if you grow several plants together for good cross-pollination.

Sesame, nigella, and paprika are also technically self-fertile but will produce much larger quantities if cross-pollinated.

– Pollinator Dependent, Self-fertile

Other spices are self-fertile because they have male and female plant parts. However, they still require pollinators to produce seeds because they can’t pollinate their own flowers without help.

Dill and fennel can both produce seeds even if you just grow one plant. Yet if not visited by pollinators, they aren’t likely to produce seeds at all. Though these plants can be hand-pollinated by you, results are much better with insect pollination.

So, ideally, you’ll have to grow these outdoors and time your planting dates so that plants will flower when pollinators are extremely active in your area.

– Cross-pollination Required

Some plants such as cumin must cross-pollinate with another cumin plant. In this case, you need the pollen from one plant to be transferred to a second plant. Though you can get seeds growing just 2-3 plants in a cluster, you’ll get better results if you plant 10 plants together to create a large patch.

This is because many pollinators collect just one type of pollen at a time. So, when you have lots of the same kind of flowering plant in close proximity, pollinators will come and stay for a while increasing the odds that pollen from one plant reaches another plant in the area.

– Special Cases

Some spices also have peculiar pollination requirements. For example, vanilla is self-fertile and pollinator-dependent when it comes to making the pods we use as a spice. Yet, cross-pollination is required for making seeds that you can plant and grow into new vanilla plants.

Also, except in its native region, all vanilla must be hand-pollinated. That’s because only a few pollinators are capable of the maneuver required to transfer pollen.

The pollen is also short-lived. So, each flower must be pollinated in the morning within a couple of hours of the opening using a toothpick.

– Pollination Problems

One more thing to know about pollination is that in spices, cross-pollination from the wrong plants can alter the flavor of your harvest. For example, if dill and fennel cross-pollinate the seeds from those plants can have off-flavors that make them less appealing.

2. Day Length and Temperature Dependence

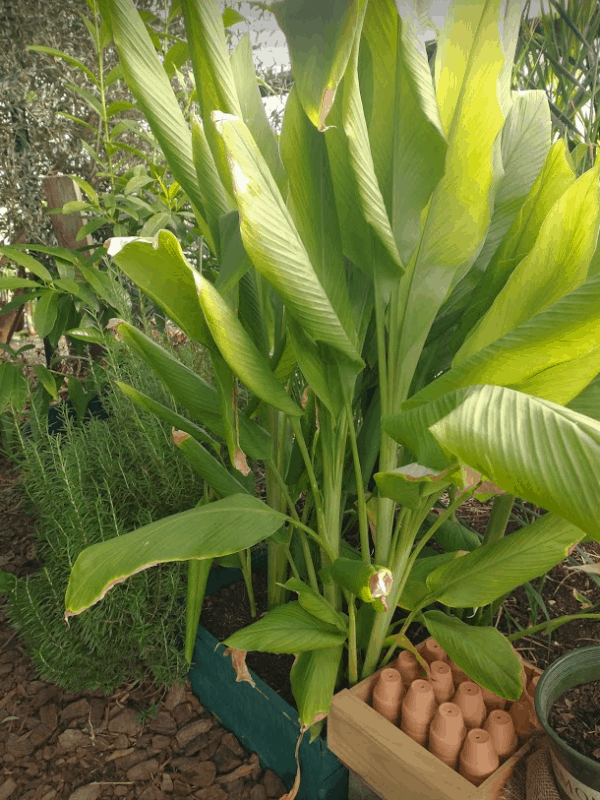

There are also several spices that we harvest for their underground stems. Ginger, turmeric, and garlic are some examples.

These plants store nutrients and sugar in fattened underground stems. However, those stems don’t begin fattening until plants have grown through a period of increasing and decreasing day length and temperature increases and declines.

– Turmeric and Ginger

For turmeric and ginger, increasing day length encourages root development. Increasing, then sustained warmth and long periods of sunlight encourages top growth. Then, shortening day length and cooler temperatures encourage the plants to begin forming those rhizomes we harvest as spice.

Without all those phases of development, the plants won’t produce large, tasty rhizomes. You can easily grow ginger family plants indoors, under lights, and even harvest small rhizomes for fresh use.

Yet, for large, long-storing ginger rhizomes to use as spice vs. as herbs, plants need to experience those natural cycles of changing day length and temperatures. Otherwise, rhizome production will be limited.

– Garlic

Garlic also needs to experience cycles like ginger family plants. However, it puts down roots and top growth best when day length and soil temperatures are decreasing. Then, it forms those underground stems we call bulbs or heads as day length and temperatures are increasing.

This is why we typically plant it in the fall and harvest it in late spring to early summer. With garlic, you can also get a harvest by planting in cool weather in spring. However, those bulbs are typically much smaller and won’t store as well as earlier planted garlic.

3. Vernalization

Some seeds spices also require a period of cold, called vernalization, to trigger flowering and seed production. Any plant that’s biennial – meaning that it flowers in its second year – requires a certain period of cold to trigger flowering. Caraway, celery, and some seed fennels are examples of this.

Some cultivars of lavender also only flower if raised in a cool period or allowed to overwinter in cool temperatures. Even capers might require some vernalization to flower, though how much is not well documented.

Becoming a Spice vs. Herb Gardener

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg of all the fascinating details involved in growing spices vs. herbs in meaningful quantities. However, if your interest is peaked, then pick a few of your favorite spices to start.

Do research to understand the spice plant lifecycle. Then try to mimic those conditions in your outdoor or indoor garden.

You may have to refine your process a few times before you figure out exactly how best to grow spices in your climate. Even so, it’s totally worth the effort to have homegrown spices wherever you live. Also, those skills you learn growing spices can translate to seed saving, flower gardening, fruit production, and more.