These days, beekeeping has grown into a utilitarian business in which bees are bought and sold without a second thought. But as food-uncertainty increases, more people are looking for ways to raise more of their own. Beekeeping is once again becoming a part of homesteading, which means learning to care for your beehives during winter.

Most of our bees are bought from bee companies and settled into Langstroth hives. We follow advice primarily designed for commercial beekeepers and assume we’ll lose a few beehives over the winter. But when you’re overwintering just a few hives, it’s time to learn to care for beehives in winter.

Bee Basics

Bees and mankind have worked together throughout our history. Humanity discovered relatively quickly that bees produce honey – a delicious, nutrient and calorie-dense food. But beekeeping has changed a lot since beekeepers greeted their hives with family announcements and asked for their advice.

Unlike sheep and chickens, bees don’t need much from us to thrive. Bees can take care of themselves. If we provide a hive, they’ll fill it with honey. More honey than a hive of bees can eat in a year.

Despite rumors to the contrary, beekeeping doesn’t have to be time-consuming or stressful. Bees are wise creatures – they appreciate our help in times of stress, but otherwise, cheerfully fend for themselves.

In fact, too many modern beekeepers undermine their hives by over-checking. It’s never a good idea to continually invade your bee’s territory to poke around. Hive inspections should be infrequent events rather than weekly intrusions. We open up our bees in the spring and in the fall, to make sure all is well.

The rest of the year we restrain ourselves – staying outside the hives and greeting our bees with respectful formality.

If you need a little primer on keeping bees, check our guide for some helpful tips.

Preparing the Hive for Winter

Unless you live in the tropics, your bees will appreciate a little support going into the cold season. Here in the northeast, our beehives face challenging weather each winter. Deep cold, harsh winds, and long, dark nights make it hard for the bees to maintain a liveable temperature.

How Do Bees Survive?

Bees spend all winter keeping the hive warm. Once temperatures fall, the hive forms a vibrating cluster with all the bees are humming and dancing. In the center of the cluster are the queen and all the youngest bees, and this cluster maintains a temperature between about 68-95°F. Even on the coldest winter nights, the bees at the center of the cluster are toasty warm.

At the outside of the cluster, the oldest bees form a crust. The oldest bees are both more expendable and more cold-hardy than the younger bees. As the weather warms, the older bees die off. Of course, bees need a lot of energy to keep their hive warm. Six months of dancing and singing would exhaust anyone. Bees get the energy they need by eating honey.

Like most northeastern homesteaders, bees spend all summer preparing for winter. Once they form a cluster, the bees aren’t able to do any of their normal hive-keeping activities. So before cold weather hits, the bees arrange the hive for winter, seal up any gaps, and open up passageways through the comb.

If left to arrange the hive in peace, bees will create an ideal space in which to weather the cold.

Can I Help My Bees Prepare?

Despite their efficiency, bees often appreciate a helping hand. If you’d like to help prepare the beehive for winter, focus on outside support. Bees know what they want from a winter hive, you know what to expect of the weather.

If you live in a place where temperatures can plunge below freezing and stay there for days, think of ways to minimize the cold’s impact on the hive. You should have set up the hives in a sunny, somewhat protected area of the yard. A spot that gets plenty of winter sunshine and is safe from the bitter north wind is perfect.

If your bees don’t have a natural windbreak, try to set one up for them. A row of trees is ideal, but if you don’t have many trees, set up a row of pallets. You can find free pallets at feed and hardware stores. Attach the pallets to posts on the north side of your beehives to protect them from the worst of the wind.

You might want to add a little bit of newspaper to the hive to combat condensation, which can freeze inside the hive.

Insulation

Right before the first hard frost, it’s time to insulate the hive. If you live in the north, and you’re using a Langstroth hive, insulating is essential. There isn’t much insulation in commercial hives, so the bees need all the help they can get to keep out the chill. Most beekeepers wrap three sides of the hive in insulation to balance the need for warmth with the need for airflow.

If you live in an area with heavy snowfall, the snow will provide an additional layer of insulation to the beehives during the winter months. But don’t trust the snow to fall before the bitter weather arrives. Wrap your hives just in case.

If you have any extra supers in the hive, remove them before winter hits. Extra supers can make a Langstroth hive drafty and harder to heat. That cluster of bees can keep a small hive warmer than a big one, so remove all unnecessary supers to make the hive tight and warm.

Removing extra supers also helps keep mice and other intruders outside. Mice love spending the winter eating honey and basking in free heating. But they’ll destroy your hive and in the spring, you’ll have a mouse nest instead of a hive of busy bees. Make the hive as mouse-proof as possible by taking out all the extra space.

Mites

If you’re concerned about varroa mites, pre-winter is the best time to treat your beehive. Varroa mites feed on the brood and they can decimate a hive. Some bee varieties are more resistant to mites, while others need a bit of help. If your bees need mite support, treat them in late fall to keep them safe all winter long.

Winter Care

Once winter arrives, avoid opening up the beehive. Right now, your bees are doing everything they can to stay alive. But don’t forget about them either!

If you’re concerned about your hive’s honey supply, it’s ok to offer them some food. Set a cake of fondant or a grease patty in the hive before winter sets in.

Unfortunately, commercial bee food can’t compete with hive-made honey and beebread. Avoid over-harvesting from your hives before winter. A healthy hive should have about 30 lbs of honey for winter, and another 20 lbs of honey to get them through early spring. If you don’t leave your bees with enough food, they’ll be anxious and undernourished.

Also, be sure to clear out any openings after a snowfall so that the bees don’t get trapped in or out of the hive.

Checking Up

If you’re concerned about your hive – after a particularly cold night or heavy storm – it’s ok to check in on them. Press your ear against the wall of the hive and listen. Can you hear them buzzing? If you can’t hear anything, try knocking.

Tap gently on the side of the hive and listen for a response. You should hear a bit of buzzing or humming from within. A healthy beehive with plenty of winter stores should be fine throughout the winter – but it’s nice to hear that reassuring buzz anyway.

Hives for Northern Winters

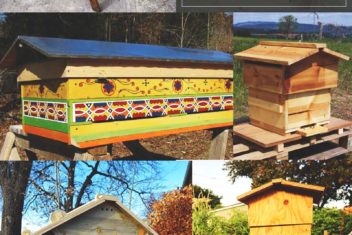

Most beekeepers across the country use Langstroth hives. Langstroth is a fantastic commercial hive. It’s incredibly easy to harvest honey from them. They’re also easy to open up and investigate. But while Langstroths are popular, easy to harvest from, and very hands-on. They weren’t designed to withstand northern winters. Instead, commercial hives are designed with the beekeeper in mind.

If you’re beekeeping in a harsher climate than USDA Growing Zone 7, consider building a horizontal hive. Most horizontal hives were designed in Russia, where small apiaries faced harsh winters. The design is based on natural, log hives.

Bees are given a large space in which to build winter-hardy hives and left largely in peace throughout the year. The horizontal hives are slightly harder to harvest from but have a year-round layer of insulation to mimic the thick layers of wood protecting a log hive.

In our own hives, we quickly switched from Langstroth to horizontal hives after losing all our bees to a bitter winter. Fedor Lazutin’s book Keeping Bees with a Smile was a great help in designing and building the hives that now keep our bees safe through cold winters and hot summers.

Helping Bees Help Themselves

Whether you stick with conventional, Langstroth hives or build a natural, horizontal hive – the goal of winter beekeeping is to support your bees as they do their best to stay alive. Over-tending to bees, either by feeding them extra sugar, or constantly opening up the hive, is going to make it harder for your bees to thrive.

Healthy hives are largely self-sufficient. They’ve spent all summer preparing for this season. A little insulation, a nice windbreak, and a lot of love are all they need to weather the storm. Winter beekeeping is full of small acknowledgments and gentle checks. It’s a good idea to visit the hives after heavy snowfall – just to ensure they’re still stable and solid.