Organic gardeners are always looking for inexpensive and effective ways to keep plants safe from fungal pathogens and nutrient deficiencies. Inevitably, if you are looking for that information in the right places, the term “compost tea” will come up quite often.

But frankly, there’s a whole lot of naysaying, confusion, and misinformation about what compost tea is, how to make it, and how to use it for the best results. This post takes an in-depth look at all the hype around this subject. Plus, along the way, I’ll give you pointers for how to safely and effectively use compost tea in your organic garden.

Note: If you’d prefer to skip straight to trying compost tea for yourself, and not worry about the controversy, check out our posts on making basic passive compost tea, customized passive compost tea using different recipes, and aerated compost tea using an electric pump.

Now, for those of you eager to understand the bad press compost tea sometime gets, and avoid controversial outcomes in your garden, let’s dig into the issues together.

1. The Two Types of Compost Tea

The first thing to know is that there are two kinds of compost tea. They are made by two different methods and have different purposes in the garden.

Unfortunately, often when people write or talk about compost tea, they don’t specify which tea of type they are referencing. That creates a lot of confusion.

So, let’s clear up those differences with a look at both teas.

Passive Compost Tea (PCT)

Passive compost tea (PCT) is made by putting well-aged compost in water and allowing it to steep for a week or two. By steeping the compost, the water-soluble nutrients are extracted into the water.

Next, you dilute this strong tea with more water and apply to plant roots as a nutrient drench. Some people also spray this on leaves where it will be drawn in through pores as a kind of instant nutrient boost.

In other words, passive compost tea on the roots is like giving plants a vitamin drink with all the nutrients being delivered in a bioavailable form the plant can instantly use. When applied to the leaves, it’s kind of like a nutrient-IV, by-passing the roots and going straight into plant tissues.

A Long History of Use

Passive compost tea has been used for so long and is supported by so much evidence, it’s not controversial (as long as you use it safely).

PCT has been proven to provide vitamins and minerals to plants. Additionally, it may confer some pathogen and pest protection in an organic garden.

But there are still a few ways people can go wrong even when using the long-trusted compost tea.

Tip 1: Apply but Don’t Fry

Be careful when you apply PCT to foliage though. Droplets of water can act as UV-magnifiers and fry your plant leaves on sunny days! Early morning, afternoon or cloudy day applications are best.

Tip 2: Apply When the Weather is Dry

Apply compost tea when you’ve got several rain-free days in the forecast. If it rains right after compost tea applications, those nutrients can get washed deeper into the soil below the root line where plants can’t reach them.

Beware: If you have shallow soil, those nutrients can actually get washed away by rain and end up polluting waterways just like synthetic chemicals do.

Tip 3: Dilute as Prescribed

Compost tea recipes are almost always brewed as concentrated formulas for easy storage. If you don’t dilute them as indicated in the recipe before applying, they can harm plants and temporarily destabilize soil.

Tip 4: Aged Compost

Contaminating your edible plants with toxic pathogens and making yourself sick is also a risk with PCT if you don’t age your compost long enough. Various research throughout the years has shown that compost should be aged a minimum of 6 months to minimize pathogen risks. Yet, some persistent pathogens can take 1-2 years to time out.

Aerated Compost Tea (ACT)

Aerated compost tea (ACT) is the second type of tea and it’s much more controversial. This type of tea has only been popular for about 30 years. Due to its newness and the knowledge required to use it effectively, it’s often misused with poor results.

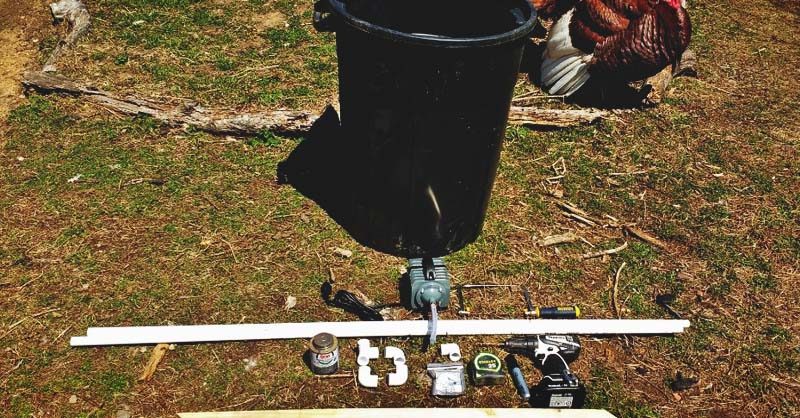

Because it takes special equipment to make, it’s frequently used on organic farms, but it’s not as commonly used on home gardens.

That means we don’t have the same body of anecdotal evidence as PCT to draw on when using ACT. Yet, a lot of organic gardeners (me included) have had huge successes using it.

ACT versus PCT

Aerated compost tea is also made by putting compost in water. But rather than passive leaching of water-soluble nutrients, a powerful pump is used to force air into the tea. That action of agitation and added oxygenation make the tea ready to use in 24-36 hours.

The basic reason for making this tea isn’t just to add nutrients (though it does). The aerated brewing process creates a perfect breeding medium for the oxygen-loving beneficial bacteria and fungi in compost. Basically, the compost used provides the microlife and the brewing process multiply them exponentially.

So, when you add ACT to your garden, it should dramatically increase the beneficial microlife in your soil. That’s a great idea in theory, but the devil is in the details as the saying goes.

2. Theory vs. Practice

Theoretically, when you apply this aerated tea to your soil and your plant foliage, your microbial population should explode. That’s a good thing because higher populations of microorganisms in soil are correlated with better pest and disease resistance, better nutrient uptake, and more drought resistance in plants.

That means if ACT actually works, your plants should be healthier, need less frequent fertilizing, and not require as much watering. Yet, I say “theoretically” because there’s not much research published to date proving that regular applications of ACT increase microlife.

Research does consistently show that the aeration of compost tea increases beneficial bacteria and some fungi populations. But, we’re seriously short on research that measures microlife populations in the soil after ACT is applied.

Microlife in Sand Study

There is one study where ACT was applied to sand as a liquid drench. The researcher said that they only had a minimal increase in microlife in the sand. That makes it seem like maybe ACT doesn’t increase microlife.

Yet expecting soil microlife to thrive in sand is pretty much like asking a human to live on drinks of mineral water. Bacteria and fungi flourish in organic matter, not inert sand particles. To me, the fact that the microlife increased at all in sand seems like evidence of how effective ACT really is at supplying microlife.

Harvard Lawn Study

Despite the lack of study-based evidence, there is a lot of physical evidence that suggests if you apply ACT and stock your soil with organic matter, the increase in soil life is phenomenal in record time.

You can tell when microlife increases rapidly because your soil gets noticeably deeper, it turns darker in color, and roots grow deeper. For example, check out some of the photographic evidence of the trials on the lawns at Harvard University to see what a difference compost plus ACT can make, even in compacted soil with heavy foot traffic.

Tip 5: Organic Matter Required

The fact is if you want those beneficial bacteria and fungi from ACT to stay put, you must continue to feed them. They eat compost, mulches like straw, shredded wood, or paper, and decaying plant matter such as from cover crops.

3. Designs for Research Dictates Results

Another thing that creates a lot of controversy around aerated compost tea is that when academic studies are done, they don’t always take into account organic gardening principles.

That example from above about microlife in sand is just one example. Here are a few more studies to consider:

Hydroponic ACT Study

I read another interesting study where ACT was used in a hydroponic system. In that study, the plants grew well in ACT and were healthier in appearance than with traditional hydroponic control solution. But the researcher had some issues with excess sodium and algae accumulation.

The researcher didn’t specify the age of the compost or the process by which it was made. However, as an organic gardener, I know the issue with sodium levels being too high happens when the ingredients used to make the compost were high in sodium at the outset.

Chemically maintained lawns, industrial crop residues grown in synthetic fertilizers, and manure from livestock fed on grasses and grains grown in synthetic fertilizers tend to be high in sodium.

The researcher also said the compost included “yard clippings”. If those were municipal yard clippings it could easily explain the algae issue. Runoff from the chemicals and fertilizers used in the average American yard is already known to produce toxic algal blooms in waterways.

Tip 6: Match ACT Ingredients to Applications

I personally wouldn’t have used compost made from non-organic yard clippings for hydroponics. I also would only apply compost made from things ingredients known to accumulate sodium to plants with a tolerance for it like a lawn, rye, or barley.

So, at home, you don’t want to use any old compost to make ACT. You want to think about the ingredients used to make the compost, the method it was made by, and then match it to the right plants and soil types.

The challenge is, it takes a lot of research or a lot of experience making many formulations of compost before you can make those kinds of decisions about which compost will and won’t work in various ACT applications.

That makes it tough for a beginner to figure out. Luckily, there’s another way to get it right.

Tip 7: Make Balanced Compost at Home

Just make your own compost at home. The balanced compost you make with a mix of kitchen scraps, manure from more naturally raised livestock, your own organic grass clippings, and crop residues from your garden likely won’t result in sodium accumulation, or algae producing issues faced in that study.

To make balanced compost:

- Get your carbon to nitrogen ratios right.

- Keep your pile aerated and properly moistened.

- Use a lot of ingredient variety in the mix.

ACT made with that kind of compost, after it is aged, will be effective for most applications.

Tomato Study

In another study on tomatoes, the researcher detailed the exact methods by which the composts (garden waste compost and vermicompost) were made (turned pile) and age of the composts (180+ days).

They also provided a detailed analysis of the extraction method, application rates, nutrient content, and pathogen profile of the teas. That’s super helpful in case someone wants to repeat the experiment.

Plus, their clearly summarized results showed the following:

- Their ACT had a high level of nutrients, such as N and K, which contain phytohormones IAA and salicylic acid, humic acids, and microorganisms.

- The garden waste compost had a high suppressive effect on F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fusarium wilt) whereas vermicompost tea achieved a better result in controlling R. solani.

To me, that study looks like they used exactly the right kind of compost. Unfortunately, they said they brewed the tea for a week and only aerated it 4 hours per day which seems like a mistake to me.

Tip 8: Provide Oxygen Consistently

When you turn on the aerator for 4 hours, good bacteria populations increase exponentially. Then, when you turn it off, all those new bacteria keep on using oxygen.

In short order, without aeration, they’ll either suffocate or go dormant after they deplete the tea of oxygen. Once the oxygen is gone, that stagnant environment makes it easier for bad bacteria to thrive and reproduce.

That compost must not have had many pathogens, so the researcher got lucky. But if you are going to aerate, do it for the full 24-36 consecutive hours prescribed by ACT experts.

Regular ACT users leave aerators on the entire brew time to ensure that the microorganisms always have sufficient oxygen. Cycling it on and off increases safety risks and decreases microlife production.

Also, using too small of a pump, in too large of a water vessel can make ACT into a pathogenic problem. Storing ACT for more than a couple of hours after turning off the pump is also a potential problem.

Instead, oxygenate with a sufficiently powerful pump the entire time you brew. Then use your tea within an hour or so of turning off the pump.

Bottom line: If you are going to make ACT, use the aeration methods that have been validated by long-time research and are used by professional ACT makers.

4. ACT Misapplied

Another controversy that casts dispersion on the benefits of using ACT is that some people make ACT using risky methods. Insufficient oxygenation, already discussed is a big one. But also adding unsafe ingredients or using the wrong kind of compost can all undermine the success of your ACT applications.

Here are some of the kinds of things that can lead to ACT harming instead of helping your soil.

Uncomposted Stuff

Some people add stuff like dried, but not aged manure, or fish emulsion fertilizer into their ACT to increase the nutrients. If you are certain those things are pathogen free, they are fine to use. But often, they are carriers of pathogens and can contaminate your tea.

Plant Matter

Some people also add plant matter from things like nettle or compost, which isn’t bad on its own. But if you have been fertilizing those plants with stuff like uncomposted banana peels, coffee grounds, urine, or unaged compost, they can also be a source of bad bacteria in compost tea.

Bacteria Activators

Then, if you also add a sugar source like molasses which is a feedstock for both good and bad bacteria, the bad guys tend to populate faster than the good guys. So, risky additives plus a sugar stock are an invitation to pathogen propagation.

Tip 9: Skip Risky Additives

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, it’s best that not to use any additives besides compost in your aerated compost tea.

Personally, I do use food-grade molasses. I also use organic fertilizer meals at times. But those are risks I take because I have done extensive research and am confident in my knowledge of compost and pathogens. For beginners, though, you may want to err on the side of caution and skip all extra additives.

Mushroom “Compost”

Another example I came across, in some of the failed studies done on ACT, is that researchers tried to use “mushroom compost”. This stuff is typically made by composting chicken litter, cow or horse manure, plus some woody materials, and crop residues for only a few weeks. Then that compost is pasteurized to kill bacteria.

At that point, the sterilized compost becomes a food-safe source of nitrogen, lignin, and cellulose for mushroom spores. The mycelium grows in that substrate and break down the lignin and cellulose into smaller particles, while depleting the nitrogen, to make the mushroom fruits.

The mushrooms are sold for food and the spent substrate is bagged and marketed as mushroom compost. What’s great about mushroom compost is that when you add it to your garden, because the fungi have pre-digested the cellulose and lignin, it’s now a perfect feedstock for beneficial bacteria already present in your organic soil.

But it’s not a source of beneficial bacteria since it was pasteurized to kill them. It’s also not a source of nutrients like nitrogen because those were used up in the growing of the mushrooms.

Since the point of making ACT is to create the perfect conditions for beneficial bacteria – supplied in the compost — making ACT with pasteurized compost for that is like making caffeinated tea using decaf tea bags. It just won’t work!

Tip 10: How to Activate Mushroom Compost

“As is” mushroom compost is not a good choice for ACT. But you can still use it with a little preparation. Because it was pasteurized and lacks good bacteria, you must allow it to be re-colonized by beneficial bacteria before you try to make ACT with it.

I put my mushroom compost bags in my garden under a tarp for about 10-12 months. When I open the bags, they are always full of worms and have the rich smell of mature compost. Then I know they are ready for use to make ACT.

Controversy #5: ACT Stunts Plants

One last reason there’s unnecessary controversy around ACT is that people try to use it as an instant fertilizer without understanding how it works in relation to long-term plant health.

Now, ACT does have some water-soluble nutrients. But its real purpose is to increase beneficial bacteria in the soil and improve plant root development. Those are the things we know make plants more resistant to pests, disease, and drought.

Sometimes, especially when you first start using ACT, your plants may appear to stop growing or even be stunted when compared to non-treated plants. If you look underground though, you’ll find a different story.

Plants that were shallow-rooted in poor soil, often grow significantly deeper roots when ACT is applied. For a time, they may stop growing above ground so they can invest their energy into expanding their root network.

This can be bad news for a 30-60 day annual crop because it can delay your harvest. Yet, during a dry spell, a pest invasion, or the perfect conditions for pathogen proliferation – those deeper, more soil connected roots are what give plants a better chance to thrive.

Tip 11: Apply ACT Timely

Rather than starting to apply ACT on your short-season annuals mid-cycle, begin applying it when you apply compost. Then, keep on using it regularly to promote continued plant health.

Defending Researchers

Now, I highlighted several studies to demonstrate why the outcomes of research about ACT done in labs aren’t necessarily representative of how it will work in your garden. But it’s important to note these researchers are studying this stuff to figure out how to use municipal wastes in industrial agriculture.

So, I appreciate the fact that they are trying to find ways to adapt ACT and PCT for use on larger-scale farms in lieu of toxic chemicals.

ACT Dynamically

As home gardeners, though, we get to think dynamically, rather than just focusing on isolated experiments. We also get to include PCT and ACT into our broader organic management plans. We also get to tailor their use to our soil types, plants, and precise goals.

I’ve done a lot of experimenting with both of these teas on annual and perennial plants. Here are a few more tips based on what has worked for me that may help you figure out applications for your garden.

Tip 12: Consider Vermicompost

When I make ACT or PCT for my vegetable garden, I only use vermicompost as my compost source. That’s because worms are known to have gut flora that increases beneficial bacteria and decreases fungal pathogens. Since many annual vegetables are highly susceptible to fungal pathogens, it seems like the safest choice for me.

Tip 13: Skip High Risk Compost

Also, I never use compost made with commercial crop residues for making compost tea unless it’s certified organic. Otherwise, that stuff might contain herbicides, pesticides, and fungal pathogens that can persist in compost for over two years.

If you turn that kind of potentially toxic compost into tea and apply it to plants, it makes all that nasty stuff immediately available to roots and leaf pores. That’s like weaponizing it to make plants sick immediately. No thanks!

Tip 14: Use Both PCT and ACT

Finally, in my own trials, I find PCT to be perfect for short term vegetables that are harvested in under 60-70 days. Since ACT is more work to make, I only use it on vegetables that have longer growing periods like ballhead cabbages, sweet potatoes, and winter squashes.

ACT is also my go-to for establishing new garden beds. I also love to use it for the first year or two after planting new perennial fruits or vegetables. ACT is a must in our small vineyard because without it we never get a crop due to fungal pathogens.

The Final ACT

Now, my fellow organic gardeners, you know how to make compost teas less controversial in your garden. Whether you prefer to ACT wisely or apply the time-honored traditional PCT to your garden, your soil will pay you back in easy-to-dig spades of lovely loam for that extra TLC.