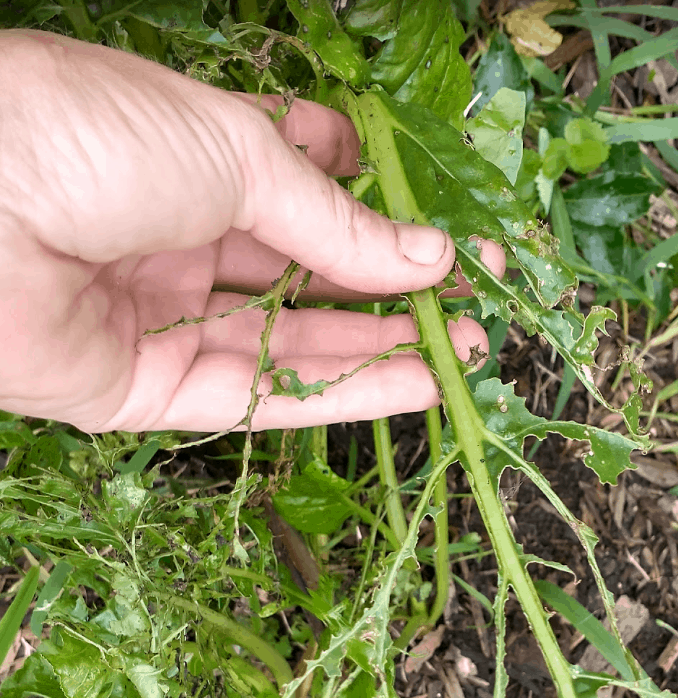

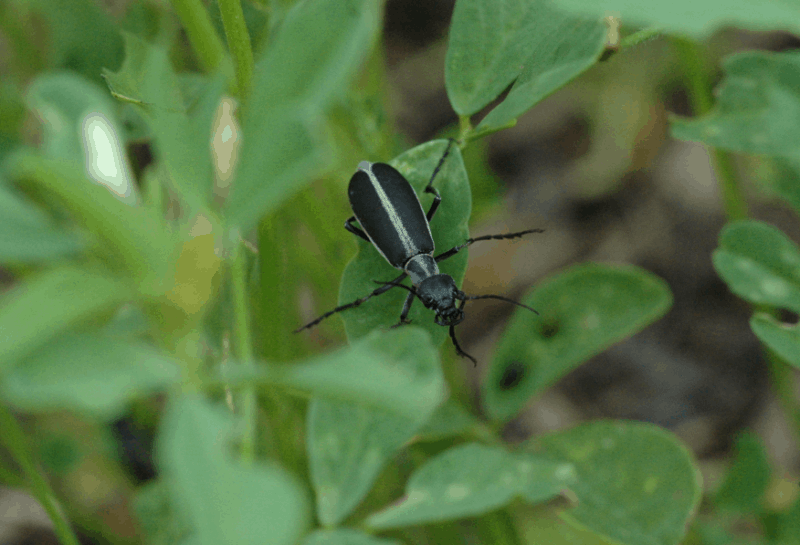

One day I walked out to the garden and noticed that the tops of an entire row of flowering potato plants had been munched down to the thick central stems of each leaf. A few partially uneaten leaves were covered with long, narrow black beetles with gray stripes.

My first thought was to put up a temporary fence around the bed and bring a few chickens over to do pest control for me. However, thankfully, I realized I better take a few minutes to identify the insect first. Turns out those leaf-devouring beetles fell into a class of beetles referred to as “blister beetles.”

As the name implies, they secrete toxins that can cause blisters. Moreover, they can be lethal to small livestock like chickens and even to bigger livestock like horses and sheep in large quantities.

About Blister Beetles

There are thousands of different kinds of blister beetles all over the world. The types that normally pose problems for vegetable gardeners and livestock keepers are both a beneficial insect in one regard and a dangerous pest in others.

The adult females lay eggs in the soil. The larvae hatch and search in the soil for the eggs of things like grasshoppers. Since grasshoppers are pesky too, blister beetle is a bit of a beneficial insect for the garden.

Unfortunately, those larvae grow up to be leaf-eaters of the crops and flowers we like to eat and enjoy. When mating and feeding in group clusters, these beetles can often do even more damage than the grasshoppers they prevented from maturing.

When you combine that plant damage with the potential poisoning hazards to you and your livestock, overall, blister beetles are considered more of a dangerous pest that you’ll want to carefully control than a beneficial insect in the garden.

1. Identification

Blister beetles all have long, soft, narrow bodies with leathery looking wings. Some are brightly colored with the yellows and reds that identify them as poisonous. However, others are black, gray, or otherwise dull in color and appearance.

Their heads are separated from their bodies by a narrow thorax. The thorax is technically the chest of the beetle. However, in blister beetles, they look very much like a long neck between a caped body and a big head. The narrow thorax and elongated body are a tell-tale sign that you might be dealing with a blister beetle.

Although only the Margined blister beetle (Epicauta funebris or pestifera) has bothered my vegetable garden, I have identified six other blister beetles on non-edible perennial plants around my homestead. There are supposed to be dozens of species where I live and over 2500 blister beetles have been identified worldwide.

Not all blister beetles are garden pests. However, since all blister beetles are potentially toxic, it’s important to be on the lookout for their distinct body type when working with plants.

2. Cause of Toxicity

Blister beetles don’t have stingers and can’t do much harm if they try to bite a human or livestock. Instead, they secrete a poison called cantharidin. Some secrete these from their legs, others through the mouth.

They do this when frightened or when squished. Additionally, the toxin may be present in the eggs and the larval stages as well.

The poison causes blisters or welts on the skin of humans or animals. It is also known to be toxic to livestock and people if ingested. It’s especially dangerous to poultry, sheep, and horses.

Damage and Risks from Blister Beetles

There are a few different ways that blister beetles can cause damage or increase risks on your homestead.

1. Garden Risks

In the garden, these insects pose risks to gardeners who may inadvertently touch or squash them with bare skin. You could also potentially harvest a blister beetle or two when you go out to cut your chard or other vegetables.

If it happened to make it into your mouth when you eat your harvest, then you could suffer blisters in your mouth and digestive tract. Also, if you use livestock in your garden, such as chickens and ducks for pest control, they can potentially eat those beetles.

Finally, since blister beetles are also voracious leaf eaters in their adult state, they can also decimate some of your plants and crops if left unchecked.

2. Livestock Feed Risks

Additionally, several kinds of blister beetles like legumes such as alfalfa and also prefer the leaves of weeds that are commonly found in crop fields such as pigweed or spiky amaranth. That means they can sometimes be found in fields of hay or in harvests of soybeans.

When that hay is cut or field crops harvested, some of these insects are also chopped up and collected with the harvest. As such, even their desiccated bodies pose a risk to the animals that may inadvertently eat the dried cantharidin toxin while munching on their meal. This can cause blistering in the mouth and the digestive tract.

Grazing livestock can also accidentally eat them while out in pasture too. Thankfully, though, this seems a less common form of transmission than contact through dried hay.

Plants Most at Risk

Blister beetles eat a diverse range of plants. Many species prefer flowering plants because they enjoy the nectar, flowers, and leaves at once. However, the most common garden pests tend to be drawn to the very same crops and vegetables we enjoy.

Their favorites seem to be anything in the beet family (chard, spinach, beets), nightshade family (tomatoes, potatoes, eggplant, peppers, goji berries), and legumes (beans, fenugreek, fall-planted peas, clover in flower).

Unfortunately, I have also seen them eat the leaves of every vegetable in my garden except plants in the brassica family. They specifically seem to avoid the mustard and horseradish that I grow in the warm season.

Lifecycle of the Blister Beetle

Since there are over 2500 known blister beetles, there’s a lot of variety in their lifecycle and how they develop. Generally, though, the blister beetles most common in your garden live for 3-5 months. However, they can even live up to a year or more in certain circumstances.

1. Climate Sensitive

They thrive in warm weather and are not very cold hardy. They do sometimes migrate into Northern climates for the growing season. However, they are mostly considered pests of warmer regions.

Additionally, in very warm climates you may get multiple generations of blister beetles per year that start reproduction earlier. In more marginal climates, you may only get one generation per year.

For example, where I live in North Carolina, USDA plant hardiness zone 7a, we see blister beetles starting in July and usually only have one generation per year. This is good news for colder climates because it makes it less likely for blister beetles to become a pervasive pest problem.

2. Overwintering

Blister beetles generally overwinter in the soil or under the protection of rocks or ground debris. They mostly survive that time period in their juvenile state.

Striped blister beetles, for example, are believed to do this during their 6th instar. An instar is a part of the development cycle when an insect molts to reveal another stage of maturity.

During development prior to pupating, these insects can slow their respiration rates to almost non-existent and delay their growth. So, in cold weather, this is what allows them to basically stay in an almost dormant limbo state until warm weather comes again.

Then, when the weather warms, the development will speed up and they’ll go through several instars before finally pupating and becoming a mature beetle. Because there are so many stages of transformation, it’s difficult to identify this pest until it becomes a fully-fledged adult.

3. Breeding

Mature blister beetles tend to mate in clusters. This is why similar to harlequin bugs or Japanese beetles, you may find a large population grouped on just a few plants.

The females then lay eggs in the soil. They will lay several egg masses that contain between 50-300 eggs each. Depending on the temperature, the eggs will hatch in about 2-4 weeks.

4. Larval Stage

The larva will seek out food. They may crawl to find grasshopper eggs. Or they can move onto flowers to lay in wait for other insects to pick them up and carry them to food sources. For example, those larvae will sometimes hitch a ride on a bee to get to their nest and feed on bee larvae.

Once the larvae have enough to eat, they’ll go through several stages of development leading up to pupating. Then, after pupating, the adult will emerge and the breeding cycle will begin again.

General Control Methods

Finding blister beetle eggs or identifying them in their larval stage is extremely difficult. So, generally, methods for controlling blister beetle populations are targeted toward the easily recognizable adults.

In particular, when you find them mating in clusters, that’s the easiest time to take action in the home garden.

1. Hand-Picking

Hand-picking is the best method of control. However, given their toxicity, you need to do this while wearing impenetrable gloves and appropriate protective clothing.

You can pick, squash, and dispose of the dead beetles in a plastic bag using your gloved hands. Then make sure to close and dispose of that bag in a safe manner.

2. Water Bowl

Alternatively, you can knock or shake the beetles into a bowl of water. I don’t like to see any critters suffer and these beetles don’t die quickly in soapy water. So, I also use scissors and cut their heads to end things quickly. Then dispose of the dead beetles by flushing them down the drain.

Also, note, these beetles seem to drop to the ground when you disturb them. So you’ll also have to pick them off the ground or visit the plant periodically several times per day for a few days to make sure you get them all.

3. Trap Plants

Supposedly these pests love flowers like calendula and amaranth. I have seen them on both plants in my garden, but they don’t seem to be favorites when other food sources are available.

They always find my fenugreek once it starts to flower, though. That might be a potential trap plant option. Just make sure to time your fenugreek planting so it will flower during their peak mating season.

From my own experimentation, they also seem to love any flower or vegetable that I plant in my goji berry patch. You may need to do some experimentation to find trap plants that work in your garden.

4. Trap the Cluster

Rather than grow a specific trap plant, though, it’s pretty easy to trap these beetles where they congregate. When you see them on a plant, you can hand-pick as described above.

Or spray those plants with an organic pesticide containing Spinosad to kill the beetles. Even if you use a pesticide, you’ll still want to do clean up to remove the beetle bodies so you don’t accidentally harvest them and ingest them yourself or feed them to your livestock.

5. Birds and Blister Beetle Control?

In researching blister beetle control methods, I came across a few organic gardening websites that recommended attracting birds to your garden to eat the blister beetles. I also found scholarly articles on wild birds suffering negative impacts from consuming cantharidin containing insects. There were also speculations that in rare circumstances birds may use blister beetles as a form of self-medication to cure illness.

Personally, I found the research to be too mixed to be conclusive. Since we know for certain that cantharidin can kill livestock and hurt humans, personally, I put floating row cover fabric over blister beetle-infested plants until I am sure I have killed them to protect my ducks and the wild birds that live in my garden.

Spanish Fly and Wart Removal

There are two more interesting facts you might want to know about blister beetles. The first is that the fringe aphrodisiac “Spanish fly” is made with the mouth secretions from a Southern European Emerald green variety of blister beetle.

Spanish fly has been banned just about everywhere because it has proved lethal to several women and caused severe cases of genital blisters. However, the use of topical cantharidin from blister beetles is sometimes medically prescribed for wart removal because it makes warts fall off.

I don’t know about you, but after knowing this, the idea of Spanish fly just doesn’t seem sexy anymore! Seriously though, blister beetles and the toxin cantharidin can be very dangerous. So, please use caution when you encounter them in the garden or elsewhere!