If you look up the history of the word Harlequin, you’ll find that it derives from the word demon and applies to a court jester type in colorful costume with a wooden sword. That someone decided to use the term “Harlequin” to describe a crop-eating member of the “true bug” family is no accident.

Harlequin bugs have very distinctive markings that make you think back to the days when lords and ladies held highly costumed court gatherings. To me, they look like a colorful coat of arms from days of old.

Yet, as you would expect from a court jester-looking bug, they can also make mischief and mayhem in your garden.

About Harlequin Bugs (Murgantia histrionica)

True bugs belong to the Hemiptera order of insects that includes other garden pests like aphids and cicadas. These specialized insects contain mouth sucking parts that enable them to suck moisture and nutrients from plant parts including leaves, stems, and fruits.

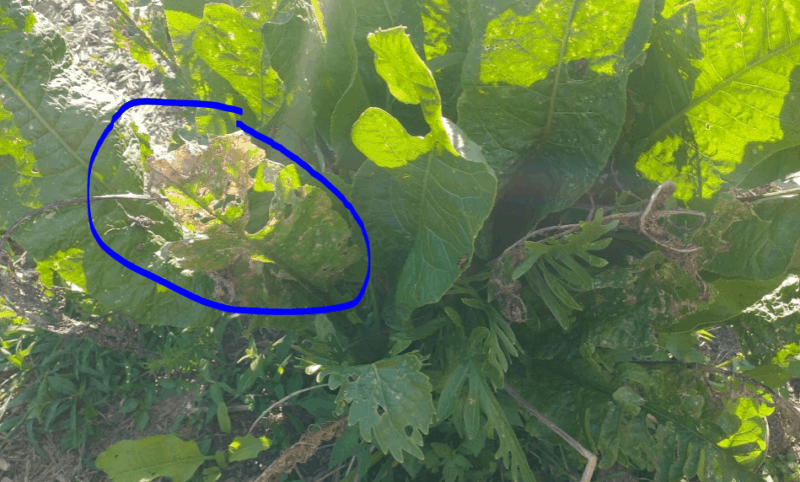

You can identify the impact of the harlequin bug’s eating habits when your plant leaves begin to thin and go papery in spots or turn a bit crispy like potato chips. Normally though, even before your leaves show damage, you can easily spot these brightly colored critters gathering collectively on your horseradish, mustard, turnips, kale, or other brassica family plant leaves.

1. Court Clusters

Like the costumed court performer they are named for, harlequin bugs are social creatures who like an audience. Whether they are breeding or feeding, they tend to do it in groups. They, in fact, excrete an aggregation hormone that attracts other harlequin bugs to the area.

So, like aphids, you often find them clustered on one plant, or a few plants situated close together, rather than dispersed around your entire garden. This can be a plus when trying to control this pest as it makes locating and eradicating them easier.

2. Colonizers

Unfortunately, gardeners often unwittingly move this pest from place to place. For example, when you pull up an infested plant, if you don’t first kill all the harlequin bugs before moving it to your compost pile, you can inadvertently relocate them to a new home along your path.

One harlequin bug couple can create 4-5 generations per year in warm climates. Then, those new generations can reproduce at the same rate. In warm areas, that means you can end up with over 10,000 new harlequin bugs starting with just a single male and female.

3. Predator Resistant

The harlequin bug is also a member of the narrower superfamily of bugs called Pentatomoidea. These bugs are commonly referred to as shield bugs or stink bugs.

Their abilities to excrete foul-smelling liquid from scent glands and the hard shield-like exoskeletons make them less prone to predation than many other garden pests. Unfortunately, those two effective defense methods mean that harlequin bugs, and other shield bugs, have fewer natural predators in the garden.

So, even for gardeners who normally just let nature take its course, this is one pest you will want to proactively help nature control. Otherwise, you should expect heavy damage to your brassica plants.

Damage from Harlequin Bugs

Damage from harlequin bugs can vary depending on how big the infestation is. In the early forms, it just looks like the leaves are pocked. Then, as the leaf tissue fails to get nutrients, it begins to dry out. Left unchecked, entire leaves can die and ultimately the entire plant.

In a typical case though, the bugs seem to prefer to eat only part of a leaf then move to a new leaf. So, the damage is often dispersed across many leaves on the same plant.

Plants at Risk

Horseradish and mustard leaves are the all-time favorite plant choice of Harlequin bugs in my garden. However, I have also found them on every brassica family plant including kale, chinese cabbage, ballhead cabbage, rapini, turnips, daikon, kohlrabi, broccoli, cauliflower, and others.

In hot weather when cool-season brassica plants aren’t available in many gardens, these bugs will turn to just about any other vegetable or fruit you have. Legume leaves seem to be their next favorite, followed by cucurbit leaves, and then sweet potatoes.

Cleome flower is also a favorite. However, they will also eat grape leaves, lettuces, strawberries, and others if your garden doesn’t contain any preferred plants.

Life Cycle of Harlequin Bugs

Harlequins are warm weather bugs. They will be killed by extended freezing cold.

As such, they usually only overwinter in areas with moderate winters such as where I live in North Carolina. When they appear in more northern climates it is usually because they came in on plants.

1. Overwintering

Experts don’t think these bugs hibernate. Instead, they just stay warm near the surface of the soil feeding on fallen plant matter through the colder months. I have personally seen them crawling in my garden soil in mid-winter on warm days following freezing days.

When it warms up for several weeks, they resume their normal feeding and breeding cycles.

2. Breeding

Harlequin females live between 50-80 days. Males tend to have shorter life spans, likely because they do more traveling and are more subject to predation as a result.

It takes 30-50 days for a female to reach reproductive maturity. They mature faster in warmer weather and can begin laying sooner in hot conditions. So, that’s why you can go from having a small harlequin bug problem in early spring to a big one in summer as temperatures rise.

– Adult Appearance

The adults look like they’ve been painted to resemble an orange or red, black, and white-colored crest on a medieval knight’s shield. They are about the size of your fingernail.

They fly short distances. However, they mostly walk to get from place to place which makes them easy to knock into a bowl of water.

– Caught in the Act

These garden pests mate rear to rear. Once they latch on, they stay joined until mating is finished. Essentially, if you can catch them in the act, you can easily kill the male and female simultaneously.

– Female Homebodies

Females may stay on the plant they were born on for their entire life cycle if the food is good. Males are more likely to migrate to find females on other plants once mature.

If you think about it, that makes good sense as a way for nature to encourage genetic diversity among these bugs.

3. Egg Stage

Once they hit maturity, females can lay about 12 eggs every 3 days until they die. If only our chickens could do that – a dozen eggs every 3 days. Can you imagine?

Those eggs hatch between 4-29 days. This also depends on temperature. Warmer weather makes for faster hatch rates.

– Egg Identification

The eggs are barrel-shaped with alternating black and white stripes. They look a whole lot like a black and white version of the Cat in a Hat to me. They are generally in clusters of about 12 eggs found mostly on the undersides of leaves or in shady parts of the plant.

– Egg Control

Several kinds of garden spiders feed on the eggs. In fact, they are the primary natural predators that help to control populations of harlequin bugs in home gardens. Mulching beneath plants will provide habitat for spiders.

4. Nymph Stage

At the nymph stage, these bugs don’t have wings. They do all their traveling on foot. Generally, they start feeding close to the egg clusters until everyone hatches. Then they may expand their range as a group.

– Nymph Identification

The nymphs look like small versions of the adult harlequin bug in color with more striped-like markings. They are also more rounded in shape and don’t have wings.

– Nymph Predators

At this stage of life, there are a few pest parasitic wasps that might help you control your young harlequin bug populations. I’ve also seen lady beetles, praying mantises, assassin beetles, and predacious stink bugs devour the just hatched harlequin nymphs in my garden. However, they generally don’t get them all.

– Nymph Control

So, you’ll also want to drown or squash any nymphs when you see them. I crush them with my bare fingers. However, as a precaution, you may want to wear gloves or use another leaf to sandwich the bugs to squash them to protect your skin from possible irritation.

General Control Methods

In addition to doing manual control by squashing or drowning your harlequin eggs, nymphs, or reproductive adults when you see them, there are some other control methods to use.

1. Trap Plants

Because harlequin bugs are warm weather breeders that congregate to mate, you can use that against them. By planting a mustard plant in the center of beds that have had harlequin bugs in the past, you can draw them to their favorite food source and away from your other crops.

Then, you can kill them as you see them. Or, you can treat the entire plant with organic pesticides.

2. Pesticides

Your basic arsenal of organic pesticides will work wonders on harlequin bugs. For example, neem oil sprayed directly on them, products containing Spinosad, or insecticidal soap will all do the job.

Just beware, when you use any product on your plants, you will also deter beneficial pests such as pollinators. For plants that are pollinator-dependent, make sure to hand pollinate after treating with pesticide. Or, go back to hand picking until your flowers are pollinated.

3. Maintain Healthy Plants

Generally, the number one thing to do to control pests is to keep your plants healthy in the first place. Stressed plants are more likely to attract pests and harlequin bugs love stressed plants as hosts.

– Plant Timing

These bugs have a particular knack for using the stress chemicals released by the plants they feed on as a defense mechanism to protect themselves from predators. This is one big reason these bugs prefer to inhabit cold weather plants grown in warm weather because those plants are sending out distress signals.

Even more than with some other insects, by culling any old or stressed plants and taking great care of plants you want to keep, you can make harlequin bugs more susceptible to predator attacks. That in turn can help reduce their population and slow down their mating cycles along with hand picking.

4. Crop Rotation and Clean Up

Also, as with all pests and diseases, prevention is key. By rotating your crops and destroying infected plants and crop residues you can go a long way toward keeping populations in check.

Also, because these bugs aren’t cold-hardy, by raking back your winter mulch on extremely cold days, you can remove their shelter and expose them to life-threatening cold. This can be a useful tool in a bed that was heavily infested the year before.

Honorable Efforts

Harlequin bugs can be a big problem, especially in areas with mild winters. However, by acting early to reduce their populations when you see them, you can keep them in check. Even if they do get a foothold, trap plants and diligent hand picking can go a long way toward control.

In extreme cases, pesticides may have to be employed. However, from personal experience, unless you are growing monocrops of brassicas in your home garden, you aren’t likely to need more than an honorable effort using organic methods to keep this coat of arms wearing harlequin bug from doing too much mischief in your garden.